A piece I wrote for Religion News Service about the Alta Fixsler case can be read here.

A piece I wrote for Religion News Service about the Alta Fixsler case can be read here.

An essay on the misrepresentation of the Jewish view of abortion was published by Religion News Service, and can be read here.

Were a donkey to suddenly develop the power of speech and address me, I would, I’m quite sure, be flabbergasted.

Faced with just such an asinine address, though, Bil’am isn’t struck silent and doesn’t collapse in shock. In fact, he seems entirely unfazed, and simply reacts to his donkey’s protest — “What have I done to you that you struck me these three times?” — by responding “Because you mocked me!” (Bamidbar 22:28-29).

What occurs to me as a possible explanation of his nonchalance is that he had become so oblivious to the difference between animals and humans — and indeed related to his beast as a partner in life — that the shock factor simply wasn’t there. True, the donkey had never spoken before, but maybe the animal simply hadn’t had anything to say until then.

The view of man as a mere fur-less ape is evident, too, at the end of the parsha, where the idolatry of Ba’al Pe’or celebrates the base physical functions that humans and lower creatures share in common.

The idea that humans are a mere subset of the animal kingdom has been taken by celebrated “ethicist” Peter Singer to its logical conclusion. Human infants, he has said, are “neither rational nor self-conscious,” and so, “The life of a newborn is of less value than the life of a pig, a dog or a chimpanzee.”

Equating humans and animals, which is common in our times as well as in ancient ones, isn’t just a means of legitimating debauchery.

It is nothing less, when truly internalized, than a prelude to murder.

© 2021 Rabbi Avi Shafran

I have defended Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez on a number of occasions in several public venues. But I was chagrined by her reaction to the recent Hamas/Israel war, and express why here.

My most recent Ami column can be read here.

Even those of us with limited exposure to farm animals can easily differentiate between a cow and a donkey. Which leads Rashi to explain that when the Torah refers to our need to differentiate between the meat permitted for us Jews to consume and that which is prohibited, it means distinguishing between things like “a trachea [of a permitted animal] that has been cut exactly halfway across [which doesn’t satisfy the requirements of shechita] and one that has been more-than-half cut.”

A rather fine distinction, of course, a matter of a millimeter or less.

Rav Shlomo Yosef Zevin, zt”l, sees it as a template for judgments to be made throughout our lives. There is a mere hairsbreadth’s difference between holiness and its opposite, he notes in his sefer LaTorah V’lamoadim. He cites the Talmudic account of Rabi Meir’s recollection of Rabi Yishmael’s words upon hearing that Rabi Meir was a sofer. “My son, be very careful in your work… for if you omit a mere letter or add one [which, in certain cases could radically change the meaning of a word], you could destroy the entire world.”

Similarly, Rav Zevin notes, we are enjoined to see ourselves as if we are half-worthy and half-unworthy; and Rabi Elazar ben Rabi Shimon adds that the world itself can be dependent on its merits outweighing – even by a single mitzvah – its demerits. And so, with each decision we make, we should imagine that only choosing correctly will preserve the world.

Even a mere momentary thought can be that crucial element, he adds, since a marriage effected by a man who betroths a woman “on the condition that I am a completely righteous person,” but whose subsequent actions indicate otherwise, requires a divorce to be dissolved. Because, as the Gemara says, “perhaps he had a thought of repentance” when he betrothed the woman on the condition.

The words of Robert Frost, in his famous poem, “The Road Not Taken,” come to mind.

“Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.”

We often make decisions in our daily lives without considering that our choices could be potentially life-changing, even earth-shattering.” But, in fact, any of them could be.

© 2021 Rabbi Avi Shafran

Sometimes money amassed through questionable means is donated to good causes like charities or educational institutions. Perhaps the donors’ subconscious, or even conscious, intent is to somehow render their ill-gotten gains “kosher” in some way.

The Zohar informs us of the folly of such thinking.

On Moshe’s exhortation near the beginning of parshas Vayakhel that the people donate materials for the construction of the Mishkan — “Take from yourselves a portion for Hashem…” (Shemos 35:5), the mystical text states:

“From yourselves” — from what is [truly] yours, not from [what you have obtained from] usury and not from [what you have obtained from] theft. Because if it is [obtained through unethical means, the giver] has no merit, but, on the contrary, woe to him, as he has come to recall his sin.”

Not only would the Mishkan’s holiness have been compromised if any of the precious metals or fabrics used for its construction were besmirched by its donor’s bad behavior in obtaining it, but also, any donation of wrongly obtained material would be a reminder of the donor’s sin.

The same point is said to have been made, particularly pointedly and wittily, by the Kotzker Rebbe, on Chazal’s statement that, at Sinai, the people saw with their eyes what normally could only be heard with ears. That way, allegedly said the Kotzker, there would be no way for anyone to hear the lo (“Thou shall not”) in lo signov — “Thou shall not steal” — as being spelled lamed-vav, meaning, “For Him, steal.”

It would seem that the notion of justifying economic crimes with virtuous use of ill-gotten gains is nothing new. It existed in the 19th century — and even in Biblical times.

© 2021 Rabbi Avi Shafran

Describing our ancestors’ worshipping of the egel hazahav, the golden calf, the Torah relates that “Early next day, the people offered up olos [burnt offerings] and shelamim [peace sacrifices], they sat down to eat and drink, and then arose litzachek [to enjoy themselves]” (Shemos 32:6).

The legendary Novardhoker Maggid, Rav Yaakov Galinsky, zt”l, would comment in the name of an “early master” that the order of the happenings in that pasuk is significant, and has broad historical pertinence.

The egel hazahav, he explained, was the first veering of the Jewish people away from Hashem, the first Jewish pursuit of a foreign-to-Torah ideal, one that bordered on idolatry. But it is an unfortunate prototype for other such ideal-idolatries in subsequent times.

Many a social movement has been birthed or eagerly embraced by Jews. And each began with with a lofty ideal, a figurative olah, a sacrifice entirely consumed on the altar, signifying selfless devotion.

With the passage of time, though, the heady days of every “ism”’s youth give way to a more jaded, or at least “realistic,” approach, signified by shelamim, a sacrifice where the supplicant is able to enjoy some of the meat. The high ideal, of course, is still heralded as paramount, the flag of altruism still flies, but there is an expectation of some “return on the investment” in the cause.

And then come the final stages, when the loftiness of the movement’s revolutionary goal deteriorates into “eating and drinking” — where self-interest and a “what’s in it for me?” mentality reigns — and, ultimately, a litzachek frame of mind, when materialism and lust become the society’s entire foci.

The golden calf was the first worshipped ism, but it was far from the last.

© 2021 Rabbi Avi Shafran

Rabbi Avi Shafran

One would have been forgiven for assuming it an elaborate Purim joke. In fact, assuming otherwise would have strained credulity.

But credible, unfortunately, it is. “It” — a new glossy magazine I prefer not to name, aimed, its marketing team says, at Jewish “men age 25-65 from the right and the left who are Conservadox, Modern Orthodox or Yeshivish; and live in Flatbush, Lakewood, the Five Towns and Bergen County” — is apparently all too real, a crazy cartoon come to life.

The new periodical is for you. If, that is, you “are enthralled by men’s luxury and higher end products.” If so, the mag “has it all covered for you,” focusing on “all fine goods in the consumption industries for Jewish men,” from “an old fashion [sic] to bourbon or wine.” And, of course, cigars, grilling, cars, cologne, man caves and fancy watches.

And there will be photos! Of “first class dining, men’s hobbies & lifestyle,” depictions that will “captivate our readers [sic] attention for their elegant experience,” whatever that is supposed to mean.

An article in a Jewish newspaper about the new offering helpfully informs readers that “Sure, you have your chavrusas, seforim and shiurim,” but you need help to “make the best use of your precious free time, with premium content by experts in their fields about the rewards that come after a hard week of work and learning.”

Maybe it is a Purim shtick.

No, I checked again. It’s not.

Something is rotten in the state of Orthodox-ish. The “ish” is indicated because hedonism is as mixable with authentic Orthodoxy as cool spring water is with grease dripping from a succulent steak on a high-end barbeque grill.

Interestingly, in response to the ongoing Covid crisis (and thankfully unaware of the magazine’s debut), the members of Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah recently issued a call to the Jewish community to recognize that the crisis’s challenges and tragedies should be regarded as “an appeal from Heaven to correct our ways,” in particular with regard to “a fundamental and broad point.”

The point? That “Klal Yisroel is a ‘nation of princes and a holy people’.” And that Jews must, as a result, “distance themselves from the pursuit of excess.”

“There are among us,” the call to sensitivity continues, “those who, notwithstanding their care with mitzvos, pursue fine foods and expensive vacations; they boast of their clothing and furniture,” people who are not exclusively focused, as Jews should be, on living “a modest life centered around Torah, service to Hashem, and kindness to others; a life purposed on being close to Hashem.” Who ignore the “spiritual danger” of “a life of materialism.”

There are, to be sure, occasions when somewhat “fancy fare” may be excusable, for the enhancement of simchos and such. There are even times when we might need to pamper ourselves in order to revive our emotional energies, when treating ourselves to a special treat helps us to better serve Hashem bisimcha. But elevating luxury to an ideal, putting hedonism on a pedestal? Ugh.

The Moetzes members’ call will probably strike the new magazine’s machers as wildly preposterous, even insane. Just like the glassy-eyed fellow with the tin foil hat walking down the street mumbling to himself about Martians thinks everybody else is deranged.

As it happens, though, the Moetzes statement should stimulate introspection in the rest of us, too, we who don’t salivate at the prospect of a good bourbon or fine cigar. We may not be “enthralled by… luxury and higher-end products,” but can we say we haven’t drifted a bit from modesty toward excess ourselves?

Things that once were extravagant luxuries have bizarrely morphed into “necessities.” Larger and more elaborate homes than we really need testify to such change (not to mention that they draw resentment from others). The sort of cars we drive, the type of vacations we take, the foods and drinks we consume, the size and elaborateness of the simchas we host (something the current health crisis has in fact taught us are unrelated to true simchah) — all point to an imbalance in priorities.

Even, at least in some places, rewards given to talmidim and talmidos by rabbaim and moros have become extravagant; stars on charts and small tchotchkes no longer cut the mustard (even our mustard doesn’t anymore, having yielded to gourmet condiments).

Some candymen in shul have reportedly also felt the need to “upgrade” their offerings, lest the youngsters find more rewarding places for worship (or whatever).

Rewarding deserving children is undeniably important, yes, but so is teaching them about limits.

It’s a truth universally acknowledged in principle but increasingly ignored in practice: Even in times of plenty and even for the financially fortunate, there is dignity in modesty.

And the opposite in the opposite.

© 2021 Agudath Israel of America

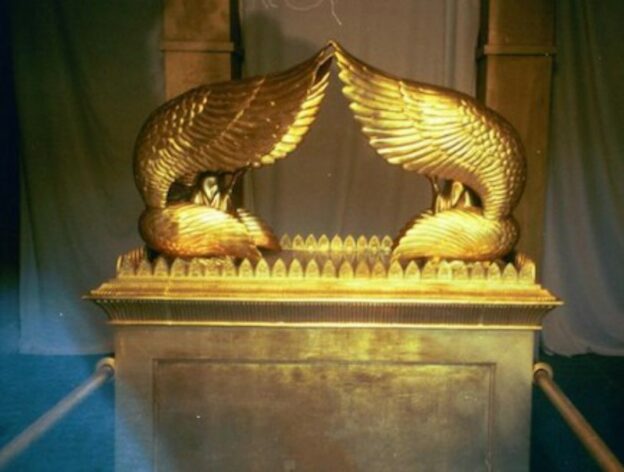

The aron habris, the holy ark described in the parshah, was essentially a wooden box set into a golden one, with another golden one set inside it (Yoma 72b).

The Gemara (ibid) sees in the aron, which contains the luchos, shivrei luchos and a Torah scroll, a metaphor for the coherence of conscience and behavior that defines a true scholar. “A talmid chacham,” Rava teaches there, “who isn’t tocho kiboro,” — whose inside [essence] isn’t like his outside [the image yielded by his behavior] — “isn’t a talmid chacham.”

My revered rebbe, Rabbi Yaakov Weinberg, zt”l, noted that the Gemara’s wording is pointed. We are not exhorted to bring our “outsides” into line with our “insides” – to first achieve purity of heart and then display its signifiers – but rather the other way around. We act properly to first emulate the comportment and behavior of those more spiritually accomplished than we are — to present an image of observance and propriety– even if our souls may not be as pure as our clothing and actions seem to declare.

That is because, in the Sefer Hachinuch’s words, “A person is affected by his actions.” How we dress, speak and act can change who we are.

Achieving coherence of appearance and heart should be the ultimate goal for us all. But we shouldn’t feel hypocritical or despondent if we show the world a better image of ourselves than we deserve. What matters is only that we are working to bring our inner selves into line with our outer ones.

What’s more, according to a Midrash brought by Rashi on the posuk uvicheit yechemasni imi (Tehillim 51:7), Dovid Hamelech lamented the fact that when his parents conceived him, their intent was basically selfish (a thought reflected as well in his words ki avi vi’imi azovuni, Tehillim 27:10). And yet, Dovid’s father was Yishai, who (Shabbos 55b) was without sin!

The inescapable conclusion is that self-interest isn’t sin. The essential sense of self is inherent in being human, and no contradiction to righteousness.

That, too, is reflected in the aron. It was gold within and without, yes, but there was wood (perhaps hinting to the eitz hadaas) between the golden layers. One’s toch and bar can be pure and consistent, but there is always a self in the middle.

© 2021 Rabbi Avi Shafran