Among the vilifiers of Israel as an illegitimate “colonial” power—and the line is long and motley—are some Native Americans.

Emphasis is on the word “some.”

To read about some other, more perceptive, indigenous people, please click here.

Among the vilifiers of Israel as an illegitimate “colonial” power—and the line is long and motley—are some Native Americans.

Emphasis is on the word “some.”

To read about some other, more perceptive, indigenous people, please click here.

Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito was born in Trenton, New Jersey, is 74 years old… and… sit down if you must… is a social conservative!

Who knew?

To read why I wax somewhat cynical regarding that revelation, click here.

The Torah’s narratives are pertinent to every generation. But certain accounts resonate particularly blatantly in certain times.

Like the saga of the ma’apilim, the “insisters,” those Jews in the desert who repented of having spoken negatively of Eretz Yisrael and insisted, even against Moshe’s warning, on short-circuiting (pun intended) the prescribed years of desert wandering and “going up” into the Holy Land immediately.

Some, like the Munkatcher Rebbe Rabbi Chaim Elazar Spira, a fierce opponent of nascent religious Zionism during the early 1900s, saw in the ma’apilim a precursor of “those sects that went up to Eretz Yisrael by force to establish colonies and wage war against the nations.”

Rav Tzadok HaCohein, who died in 1900, had a very different approach. He wrote that the ma’apilim felt that, despite the warning against going directly into the land, it was a case of “Whatever the host tells you to do, heed him, except when he says ‘leave’” [Pesachim 86b].

Although the provenance of that text’s final phrase – “except when he he says ‘leave’” – is questioned by some commentaries, the idea Rav Tzadok means to convey is that the ma’apilim felt justified in disobeying the Divine order, that their plan was in fact ultimately consonant with the Divine will.

But, while they had a point, Rav Tzakok continues, it was not the right time for such brash action. Noting the first word in Moshe’s admonition that “it [the plan] will not succeed,” Rav Tzadok writes: The word ‘it’ is often interpreted by Chazal to mean ‘it, but not another,’ [here] implying that at another time [in history] ‘it will succeed’.”

And, he concludes, “that is our time, the era leading to Mashiach.”

That era has proven prolonged. And the state of Israel is a reality. The question of whether its establishment was a wise endeavor or a dangerous one is moot today. We can only hope that the redemption Rav Tzadok saw implied by the pasuk – even if it didn’t take place in the 1900s – will happen soon, speedily, in our days.

© 2014 Rabbi Avi Shafran

Professor David Himbara called South Africa “a classic case of a de facto one-party state with mismanaged institutions and endemic crime and corruption.” It’s also a state with much racism and anti-Israelism. Its president, Cyril Ramaphosa, has been a driver of those sins. Is there hope for the future? My thoughts are here.

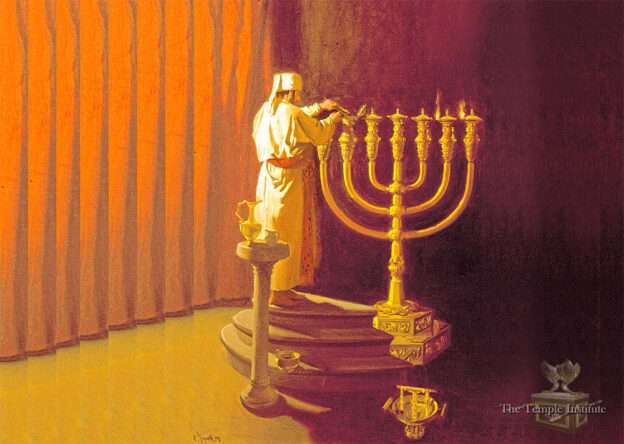

Something special about Aharon HaCohein is telegraphed in the sentence “And Aharon did so,” after Moshe’s brother receives instructions about lighting the menorah in the Mishkan (Bamidbar 8:3). Rashi, paraphrasing Sifri, comments: “This tells us the praiseworthiness of Aharon, that he didn’t change [anything in the service].”

Well, of course he followed Divine orders carefully, puzzle many commentators. What is the significance of stating the obvious fact?

An interesting approach is offered by the Chasam Sofer. The Talmud, he points out, describes the daily schedule of service in the Mishkan and Beis HaMikdash and notes, inter alia, two things: that the menorah-lighting takes place simultaneously with the burning of the afternoon incense on the mizbei’ach haketores (Yoma 15a); and that the cohein bringing the ketores would become wealthy as a result of performing that service (Yoma 26a).

Thus, suggests the Chasam Sofer, Aharon’s “not changing” means that he never took a day off from the menorah-lighting, which he could have allowed someone else to do, to take advantage of the wealth-producing ketores-offering. In other words, he shunned material gain that was available to him.

A simpler approach is taken by R’ Simcha Bunim of Peshischa, who interprets Rashi’s comment as “And Aharon didn’t change himself.”

“Power tends to corrupt,” British historian Lord Acton famously wrote in 1887. That adage – as true about fame and privilege as it is about power – has been borne out by countless examples since and presently.

Aharon, however, despite the new exalted status he had received, born of the special mitzvah entrusted to him, remained… Aharon.

© 2024 Rabbi Avi Shafran

The census of the Levi’im differs from that of the other shevatim, in that the latter counted only males 20 years of age or older while the former included even 30-day-old babies.

The inclusion of even infants in the Levi’im count is particularly striking, considering that the role of those counted is “mishmeres mishkan ha’eidus” – the guarding, or protection, of the sanctuary. A baby can’t protect anyone; he himself needs protection.

The most compelling explanation, offered by, among others, the Avnei Azel (Alexander Zushia Friedman, the author of the Ma’ayana Shel Torah compendium), is that the guarding here is not born of physical strength. The very existence of viable Levi’im is itself what offers protection. The security is sourced in the spiritual.

In Rabbi Friedman’s (loosely translated) words: “It is a common mistake that some make by assuming that the interests of the Jewish nation can be protected through martial and political means. Only the holiness and spiritual power of the guardians can actually offer protection… ‘If Hashem will not guard the city, for nought does the guard stand vigil’ (Tehillim 127:1)”

Rav Aharon Feldman, shlit”a, the Rosh Hayeshiva of Yeshivas Ner Yisrael in Baltimore, recently penned a heartfelt, elegiac essay about the security failures that allowed the tragedy of October 7 to happen, and how the future fate of the Jewish people in Eretz Yisrael (and everywhere) is dependent on the nation’s embracing its role as Hashem’s chosen people.

Based on the warnings and lamentations of the nevi’im, Rav Feldman imagines Hashem saying: “I… decided to wake you up with a powerful shock. I wanted you to realize that hitherto you were successful in your wars and in building up My land, not because of your cleverness or your army, but because I watched over you and granted you success. I wanted you to see that when I removed my support for you for a moment, your cleverness disappeared and your army fell to pieces.”

The essay shocked some in its straightforwardness. Stark truths are often shocking. But the Rosh Yeshiva’s rumination should not have surprised anyone. It was only the echo of Dovid Hamelech’s declaration above, and of the implication of the fact that even a baby among the Levi’im can be a conduit of Divine protection.

© 2024 Rabbi Avi Shafran

Has President Biden, as his arms delay and words of warning were described in some media, “abandoned” Israel? Or is he still the stalwart defender of Israel’s right to destroy her declared mortal enemy that he declared himself to be in the wake of the October 7 massacre?

My thoughts are here.

I have a suggestion for long-time New York Times opinion columnist Nicholas Kristof. To read what it is, please click here.

It’s an image to warm the deepest cockles of any peace-loving heart: A Gaza in peace with Israel, conducting commerce with her, with both countries exchanging tourists and economically prospering as a result. Indeed, by all logic and reason, Gazans should recognize that Hamas’ rule over the territory has brought them nothing but grief, death and destruction.

What chills those cockles, though, is that we’ve seen this play before. In 2005, 21 Israeli settlements in Gaza were unilaterally dismantled and the strip was rendered Judenrein. With the Gazan populace’s approval, Hamas quickly took charge and, well, the rest is tragic history.

Today, six months since the merchants of murder demonstrated the depth of their hatred and barbarism, Gaza’s infrastructure has been destroyed. Hospitals (aka military arsenals), schools (aka missile bases) and countless homes (some of which were just homes). Roads, sewage systems and the electrical grid – are in ruins.

Whether the unprecedented death, destruction and displacement Hamas has brought upon Gazan civilians has convinced them that supporting evil doesn’t pay can’t be known at this time.

But, embracing hope, the U.S. has called for a revitalized Palestinian Authority to administer postwar Gaza ahead of eventual statehood.

The P.A.? Please.

In Mahmoud Abbas’ kingdom of corruption in Yehudah and Shomron, government jobs are doled out to supporters; international aid enriches officials; basic services are spotty; elections haven’t been held for nearly twenty years.

Mr. Abbas, of course, was elated by the U.S. endorsement of even a “reconstituted” Palestinian Authority. And, in March, he announced the formation of a new cabinet, to demonstrate his readiness to step up to the reconstruction plate.

Tapped for prime minister is Mohammad Mustafa, a longtime Abbas adviser. He pledged to form a technocratic government and create an independent trust fund to help rebuild Gaza.

The U.S. National Security Council welcomed the development, contending that “a reformed Palestinian Authority is essential to delivering results for the Palestinian people and establishing the conditions for stability in both the West Bank and Gaza.”

The key word there is “reformed.”

The signs are hardly encouraging. According to Palestinian Media Watch, the new Palestinian Authority’s minister of women’s affairs, Muna Al-Khalili, offered praise in 2018, for Dalal Mughrabi at an event honoring the terrorist, who in 1978 led a group that hijacked a bus and murdered more than three dozen riders, including 12 children. “A quality resistance operation,” Al-Khalili gushed, proclaiming that the attack “proved that Palestinian women are capable of carrying out the most difficult missions.” The most heinous ones, at least.

And, mere weeks after the Shemini Atzeres massacre, Ms. Al-Khalili hailed the “right to resist the occupation” until Palestinians achieve “self-determination, freedom, independence in its sovereign state whose capital is Jerusalem…”

An equally disturbing member of the “revitalized Palestinian Authority” is its minister of religious affairs, Muhammad Mustafa Najem. He has called Jews “apes and pigs” who are full of “conceit, pride, arrogance, rioting, disloyalty, and treachery.” He sermonized that Muslims should “afflict the Jews with the worst torment.”

No, neither the old P.A. nor its “new and improved” version – as a bard once put it, “meet the new boss, same as the old boss” – is a path forward for Gaza. Any respectable government there will have to be something truly novel, an administration whose focus is on the wellbeing of its citizens, not on murdering citizens of a neighbor.

Could that happen?

The latest poll conducted by the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research, on March 20, showed that Gazans’ support for continued Hamas control over the Gaza Strip showed a 14-point rise over the prior three months to more than 50%.

If that reflects Gazans’ true feelings, no sane, responsible government will emerge in the territory. The only grounds for hope are the many reports of Gazans who quietly admit that they hate Hamas but are afraid to speak up.

Their fear is understandable. Hamas has warned Gazans that anyone seeking to undermine its administration of the territory will be treated as a collaborator – which, of course, means execution.

Are there enough Gazans who prefer peace to endless bloodshed and who will vote that preference in some future election?

I’m not taking bets.

(c) 2024 Ami Magazine

An “aptronym” is a person’s name that is amusingly appropriate — like that of the lawyer named Sue Yoo, or of BBC meteorologist Sara Blizzard.

I’ve got another one, at least for Hebrew speakers. To read what it is, click here.