Our ancestors were divinely commanded to gaze at a copper representation of a snake. In order to end a plague of snakebites born of their complaint about the mon (Bamidbar 21:8). Chazal explain that it wasn’t the sight of the copper snake per se that effected the plague’s end.

Rather “when the Jewish people turned their eyes upward and subjected their hearts to their Father in Heaven, they were healed, but if not, they were necrotized [by the venom]” (Rosh Hashana 29a).

So, the obvious question: Why not eliminate the middlesnake and just look directly heavenward?

Rabbeinu Bachya calls attention to the word used to introduce the (real) snakes in the account: hanechashim (Bamidbar 21:6). Not “snakes” but “the snakes.” The definite article, he says, is a reference to the poisonous reptiles that, are described (Devarim 8:15) as having been ever-present in the desert our ancestors wandered.

Rav Samson Rafael Hirsch expands on that observation, explaining that gazing at the copper snake was meant to sensitize the people to the ubiquity of snakes around them – and to the realization that when the snakes hadn’t harmed them, it was because of Hashem’s protection.

That puts me in mind of a pasuk (Tehillim 35:10) included at the end of Nishmas, the beautiful expression of gratitude recited at the end of psukei dizimra on Shabbos. “Kol atzmosai… matzil ani meichazak mimenu” – “All my bones shall say, ‘Hashem, who is like You? You save the poor from one stronger than him, the poor and needy from the one who would rob him’.”

My bones?

Parts of Nishmas describe our bodies’ figuratively praising Hashem. But those parts can be read, too, as asserting that our bodies’ functionings are themselves praises of Hashem.

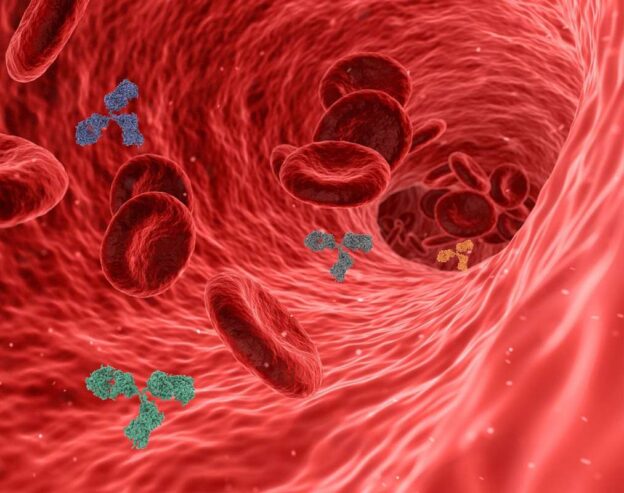

Our physical bodies are threatened by scores of dangerous invaders, held off, if we are healthy, by an unbelievably complex biological network we call the immune system.

An astounding menagerie of antibodies is produced by the white blood cells in our bodies, each product designed by our Designer to disable a specific bacteria, virus or toxin, thousands of which constantly seek to infect our bodies.

Those protectors, as it happens, are born in the marrow of our bones.

© 2025 Rabbi Avi Shafran