Easy as it is for many of us to be uninterested in schools to which we don’t send our young, there are times when disquiet, even alarm, may be warranted.

Like now. Because of a case before the US Supreme Court . Which you can read about here.

Easy as it is for many of us to be uninterested in schools to which we don’t send our young, there are times when disquiet, even alarm, may be warranted.

Like now. Because of a case before the US Supreme Court . Which you can read about here.

Faced with a forced choice between continuing to live or committing one of three sins – idolatry, murder and arayos, forbidden sexual relations – a Jew is commanded to forfeit his life.

In the case of any other sin (unless the coercion is part of an effort aimed at destroying Jewish practice), the forbidden act should be committed and one’s life preserved.

That law is derived from the phrase vichai bahem, “and live through them” (Vayikra 18:5).

The Chasam Sofer notes the incongruity of the fact that vichai bahem is written immediately before a list of arayos, one of the three cardinal sins – not in the context of sins where life trumps forbiddance. And he writes that “it would be a mitzvah” to explain that oddity.

One approach to address the incongruity is offered by the Baal HaTurim. He sees an unwritten but implied “however” between vichai bahem and what follows. So that the Torah is saying, in effect, life is paramount except for cases like the following.

A message, though, may lie in the juxtaposition itself without adding anything: that living al kiddush Hashem – “for glorification of Hashem” – is as valued as dying for it. When one is commanded to commit a sin in order to preserve his life, that, too, is a kiddush Hashem. Because in such cases, one’s choosing to live is Hashem’s will.

What also might be implied is what the Rambam writes (Hilchos Yesodei HaTorah 5:11), that the way a person acts in mundane matters can constitute either a kiddush Hashem or its opposite. If one’s everyday actions show integrity and propriety, that constitutes a glorification of Hashem’s name.

And so, perhaps, writing the words teaching us that concern for life in most cases requires the commission of a sin as an “introduction”of sorts to the imperative to die in certain other cases may be the way the Torah means to impress something upon us: the essential equality between dying al kiddush Hashem and living by it.

© 2025 Rabbi Avi Shafran

Nega’im, “plagues” that consist of certain types of spots of discoloration that appeared on the walls of a house after Klal Yisrael entered their land, signaled tzarus ayin, literally “cramped-eyedness,” what we would call stinginess. (See Arachin 16a and Maharsha there.)

Thus, the house’s owner is commanded (Vayikra, 14:36) to remove utensils from the house before it is pronounced tamei, spiritually unclean – letting others see things he has that he may have been asked to lend but claimed he didn’t have (and, by Hashem “saving” the vessels from tum’ah, demonstrating the very opposite of tzarus ayin).

The Kli Yakar explains that the words that translate as “[the house] that is his” (Vayikra 14:35), reflect the miser’s mindset, that what he has is really his. What he misses is the truth that what we “own” is really only temporarily in our control, on loan, so to speak, from Hashem.

Puzzling, though, is that Chazal also describe nig’ei batim, the “plagues of houses,” as a blessing, because the Emorim concealed treasures in the walls of their houses during the 40 years the Jews were in the desert, and when a Jew whose home was afflicted would remove the diseased wall stones, he would discover the riches. (Rashi, ibid 14:34, quoting Vayikra Rabbah 17:6).

A reward? For having been stingy?

No, but perhaps a lesson in the form of a reward.

Being stingy bespeaks a worldview, as noted above, that misunderstands that what we have is “self-gotten,” not on loan from Above. And that mistaken worldview yields an assumption: that we need to hoard what we have, lest anyone deprive us of it.

The once-tzar-ayin-afflicted homeowner, having had to remove a stone from his wall and belongings from his house, is presumably chastened by the experience. But now he is shown something to fortify his new outlook: a demonstration that wealth can come (and, conversely, go) unexpectedly and suddenly, and that we waste our energy and squander our good will by “cramped-eyedness.” We get what is best for us to have. And it comes from Above, not below.

© 2025 Rabbi Avi Shafran

The imperatives of civility and refined speech are strongly stressed in the Talmud and in halacha. Yet, like all ideals, even those have their limits. An exception – the only one – to the imperative to avoid verbalizing crude characterizations is when it comes to idolatry.

As Rav Nachman says (Megillah 25b): “All mocking obscenity is forbidden except with reference to idol worship.” And the examples the Gemara offers are almost all about defecation. The characterization of all idolatry as “avodas gilulim” in various places in Tanach may also be intended as a scatalogical reference, since galal is a word for biological waste.

And then there is the specific case of Pe’or, the major idolatry whose entire service involves hallowing the act of defecation itself.

Rav Shimon Schwab, zt”l, brings up Rav Nachman’s dictum to suggest an intriguing understanding of one of the bigdei kehunah, the “priestly garments.” Rashi points out that it seems to him that the garment is apron-like, but worn in reverse of how aprons are usually worn, tied in the front with the bib in the back.

The Gemara, Rav Schwab reminds us, assigns an atonement that is effected by each of the bigdei kehunah. The ephod atones for the sin of idolatry (Arachin 16a).

Idolatry, notes Rav Schwab, is ultimately about worship of the physical, about veneration of the base. And that is why, as per Rav Nachman’s statement, it is derided by the navi, and permitted to be derided by us, as scatalogical in its essence.

And so, he then posits, it is fitting that the ephod, the beged kehunah that atones for the sin of idolatry, is worn, oddly, in a way that covers the wearer’s lower back, subtly recalling its particular role among the bigdei kehunah.

© 2025 Rabbi Avi Shafran

There’s something puzzling about the law prohibiting a judge to take a bribe (Shemos 23:8).

The law, of course, is aimed at ensuring that a decision will be made without prejudice. As the pasuk continues, “for bribery blinds the clear-sighted, and perverts the words of justice.”

And the Gemara (Kesuvos 105a) states that, beyond the obvious wrong in a judge’s favoring one litigant over the other, the Torah is teaching us that a remuneration is sinful “even if the purpose of the bribe is to ensure that one acquit the innocent and convict the guilty,” where “there is no concern at all that justice will be perverted.”

That, too, is understandable. If one litigant offers money or service to a judge, even in exchange for only the latter’s impartial and best judgment, there is still the fact that the judge, by accepting the offer, may favor the offerer.

But the Gemara seems to say, too, that a bribe “to acquit the innocent and convict the guilty” is forbidden even if it is offered by both litigants (see Derisha, Choshen Mishpat 9:1). Presumably offered simultaneously, where there isn’t even the fact of one party being the first to offer, thereby prejudicing the case.

Why should that be? Nothing is changed by such a joint bribe to deliver a proper judgment.

It could be that there is no logical answer. That mishpat, judgment, is, in the end, a chok, a Divine ordinance, and, no less than other laws in the Torah that defy human reason, so must judgment of court cases follow the Torah’s direction, logical to our minds or not. But the pasuk’s providing a reason for the prohibition – that bribery “blinds the clear-sighted” – would seem to require some rationale here.

The best I can come up with is that the entry of any other factor – money or any other benefit – beyond the testimony of the litigants and the pertinent prescribed laws somehow pollutes the process of adjudication. Mishpat must be executed in purity, with no extraneous elements present. Anything less, puzzling though the fact may be, somehow perverts a judgment.

© 2025 Rabbi Avi Shafran

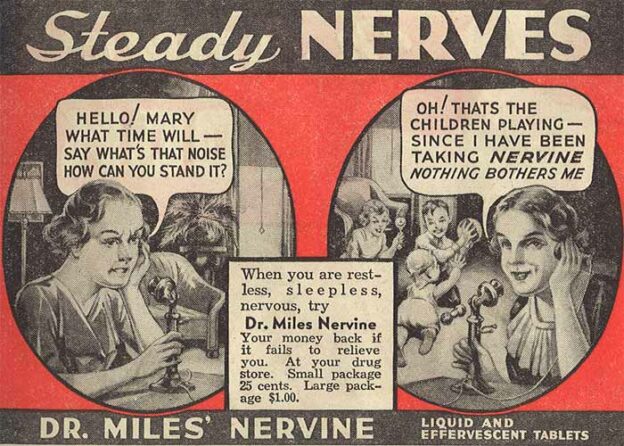

| Have you heard of Perkycet®️? No? Well read all about it, and about drug ads, here. |

For once, something positive about Israel has been served up by The New York Times, albeit unintentionally. What’s more, Al Jazeera spoke the truth.

Moshiach’s arrival seems imminent.

To read about those media’s accomplishments, please click here.

What do you think represents an “egregious threat to bedrock principles of academic freedom”?

The kidnapping and gagging of a professor? An administrator’s cancellation of the professor’s class? . A warning that he’d be fired unless he taught a certain point of view? Three strikes, you’re out.

To see the answer, click here.

Shepherds were abhorrent to ancient Egyptians, Yosef tells his brothers, as he relates what they should tell Par’oh in order to reserve the area of Goshen for his immigrating family (Beraishis 46:34). We find this in Mikeitz as well (43:32; see Rashi and Onkelos there)

Some commentaries understand that as indicating that the Egyptians protected livestock and shunned the consumption of meat. Ibn Ezra writes that the Egyptians were “like the people of India today, who don’t consume anything that comes from a sensile animal.”

Pardes Yosef (Rabbi Yosef Patzanovski) references the Ibn Ezra and explains that the ancient Egyptians considered the slaughter of an animal to be equivalent to the murder of a human being.

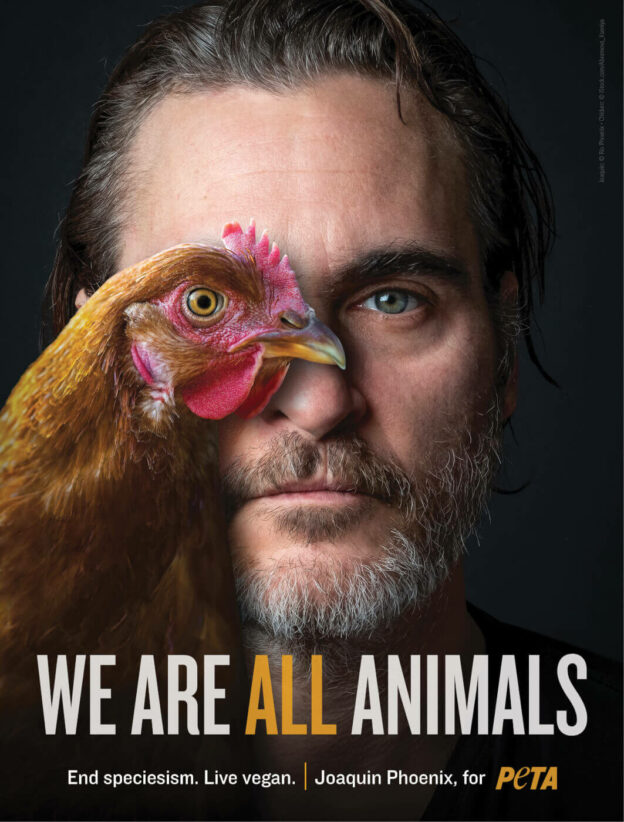

Although far distant in both time and place from ancient Egypt and India, some people in the Western Hemisphere today have come to embrace the notion that the sentience of animals renders them essentially no different from humans.

To be sure, seeking to prevent needless pain to non-human creatures is entirely in keeping with the Jewish mesorah, the source of enlightened society’s moral code. But those activists’ convictions go far beyond protecting animals from pain; they seek to muddle the fundamental distinction between the animal world and the human. A distinction that is all too important in our day, for instance, when it comes to issues pertinent to the beginning or end of life, or moral behavior.

A book that focuses on “the exploitation and slaughter of animals” compares animal farming to Nazi concentration camps. Its obscene title: “Eternal Treblinka.” Similarly obscene was the lament by People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals founder Ingrid Newkirk that “Six million Jews died in concentration camps, but six billion broiler chickens will die this year in slaughterhouses.”

But even average citizens today can slip onto the human-animal equivalency slope. American households with pets spend more than $60 billion on their care each year. People give dogs birthday presents and have their portraits taken. Such things might seem benign but, according to one study, many Americans grow more concerned when they see a dog in pain than when they see an adult human suffering.

We who have been gifted with the Torah, as well as all people who are the product of societies influenced by Torah truths, consider the difference between animals and human beings to be sacrosanct.

It is incumbent on us to try to keep larger society from blurring that distinction.

© 2024 Rabbi Avi Shafran

Imagine finding yourself in a desolate place and spying a lone figure in the distance coming toward you. Your apprehension, even nervousness, would be understandable. But then, when he comes closer and you see that it’s a man with a long white beard, wearing a hat, kapoteh and tallis, you’d breathe a sigh of relief. Until he suddenly attacks you, gets you in a headlock and bends your arm painfully behind your back.

The angel that confronted Yaakov when our forefather re-crossed Nachal Yabok to retrieve some small items looked, according to one opinion, “like a talmid chacham” [Chullin 91a].

The most straightforward takeaway from that contention is that one cannot rely on the appearance of a person as being reflective of his essence. That’s an important lesson, as it happens, for all of us, and to be imparted to our young. Honoring someone who looks honorable is fine, but trusting him requires more than that.

But there’s a broader, historical message in that image of a faux talmid chacham too.

From the 19th century Wissenschaft des Judentums movement to the Reform and Conservative ones to the Jewish nationalism that sought to replace Torah with a Jewish state to “Open Orthodoxy,” there have been many efforts to distort the essence of Judaism – dedication to the Creator and His laws for us.

They have all sought to don conceptual garb proclaiming their “Jewish” bona fides. But they have all been revealed to be no less masqueraders than the sar of Esav wrapped in a tallis.

© 2024 Rabbi Avi Shafran