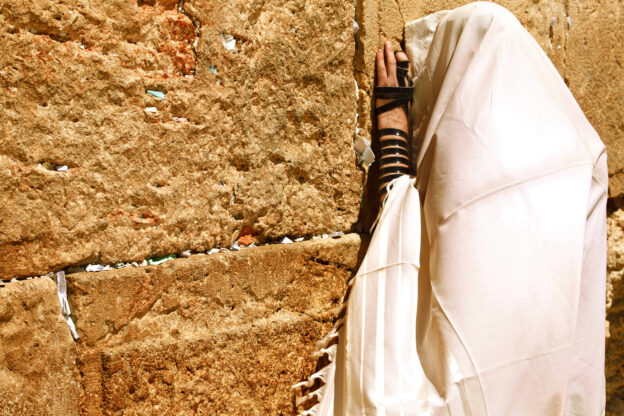

The term “afilu biShabbos shel chol” – “even on a weekday Shabbos” – is from the Zohar (Korach 179), as the end of the statement beginning: “The Shechinah has never left Yisroel on Shabbosos and Yomim Tovim…”

“Weekday Shabbos”? It has been suggested, by the Parshas Derachim (Rav Yehudah ben Rav Shmuel Rosanes) in the name of his father that the strange statement refers to the situation presented by the Gemara (Shabbos 69b) of a Jew who is lost in the desert, and who has lost track of the day of the week. There, Rav Chiya bar Rav maintains that the person should observe the next day as Shabbos and then count six days before again observing Shabbos. Rav Huna argues that he should first count six days and only then observe the first Shabbos.

In both opinions, though, a weekday could (and most likely would) end up “being” Shabbos.

The Chasam Sofer sees a hint to that approach in the fact that, in our parsha (Vayikra 23:2-3), Shabbos is counted along with holidays – as part of the mikraei kodesh (“those declared as holy”), which refers to the fact that Jewish holidays are “declared,” dependent on when the beis din announces each new month. Thus they are dependent on Jews’ actions, unlike Shabbos, which is set from the creation week and impervious to human intervention.

Except, that is, in the case of the desert wanderer. In that case, the wanderer indeed declares when Shabbos is. And the Shechinah descends on his “weekday Shabbos.”

Evidence, it would seem, of the profound power the human realm wields, able as it is to “summon” the Shechinah to descend.

Hashem has made us partners in Creation. A timely thought as Shavuos (during the month of Sivan, whose mazal is te’umim) approaches.

© 2025 Rabbi Avi Shafran