Among the vilifiers of Israel as an illegitimate “colonial” power—and the line is long and motley—are some Native Americans.

Emphasis is on the word “some.”

To read about some other, more perceptive, indigenous people, please click here.

Among the vilifiers of Israel as an illegitimate “colonial” power—and the line is long and motley—are some Native Americans.

Emphasis is on the word “some.”

To read about some other, more perceptive, indigenous people, please click here.

In my opinion, a professor at Hebrew University, when seeking in a New York Times opinion piece to divorce the Shemini Atzeres massacre from Holocaust references, missed the forest for the trees. The reason I think that can be read here.

A letter I wrote to the New York Times was published on Shabbos. It can be read here. Its text is below:

The Evil of Jew-Hatred’

To the Editor:

Re “My Son Is a Hostage. Comparing Hamas to the Nazis Is Wrong,” by Jonathan Dekel-Chen (Opinion guest essay, June 24):

Professor Dekel-Chen misses the point. The parallel indeed fails if all that is analyzed are the particulars of the Third Reich and the Hamas movement. But focusing on the trees here obscures the ugly forest: antisemitism.

The evil of Jew-hatred is a shape-shifter. It may come from political entities on the right or on the left, from one religion or another, from governments and from societal movements. And the ostensible reasons for the hatred vary wildly with time and place. But the target is the same: the Jews.

May the professor’s hostage son, and all those being held by this generation’s Jew-haters, soon be able to rejoin their families.

(Rabbi) Avi Shafran

New York

The writer is the director of public affairs for Agudath Israel of America.

There’s something strange I’ve noticed in photos of Gazan civilians. To read what it is and what it seems to mean, please click here.

Louisiana’s new law requiring the posting of the Aseres Hadibros in all public school classrooms disturbs me. Not because American children should revere the Commandments but for a different reason. Which you can read about here.

Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito was born in Trenton, New Jersey, is 74 years old… and… sit down if you must… is a social conservative!

Who knew?

To read why I wax somewhat cynical regarding that revelation, click here.

Professor David Himbara called South Africa “a classic case of a de facto one-party state with mismanaged institutions and endemic crime and corruption.” It’s also a state with much racism and anti-Israelism. Its president, Cyril Ramaphosa, has been a driver of those sins. Is there hope for the future? My thoughts are here.

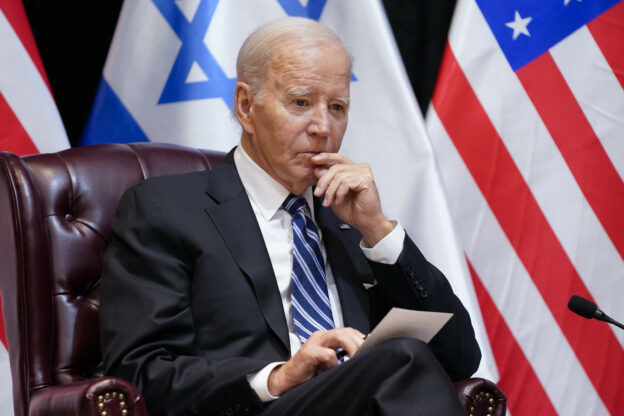

Has President Biden, as his arms delay and words of warning were described in some media, “abandoned” Israel? Or is he still the stalwart defender of Israel’s right to destroy her declared mortal enemy that he declared himself to be in the wake of the October 7 massacre?

My thoughts are here.

I have a suggestion for long-time New York Times opinion columnist Nicholas Kristof. To read what it is, please click here.

Did you hear? NPR is biased!

Who—other than any mentally uncompromised listener to National Public Radio—knew?

To read what made that revelation newsworthy, click here.