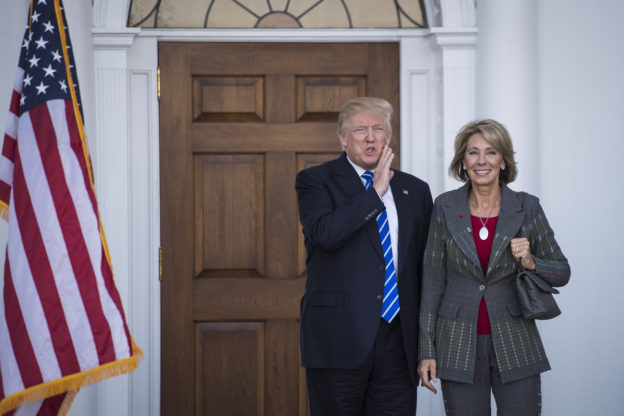

An article of mine responding to Forward contributing editor Jay Michaelson’s lament over the appointment of Betsy DeVos as the nation’s next Secretary of Education appears in that paper, accessible here.

An article of mine responding to Forward contributing editor Jay Michaelson’s lament over the appointment of Betsy DeVos as the nation’s next Secretary of Education appears in that paper, accessible here.

The sobbing of some political liberals, including, of course, many Jews, that ensued after the presidential election results were tallied has turned into wild wailing with the appointment of Stephen Bannon as senior counselor to the president-elect.

Those observers were shocked enough back in August, when Mr. Bannon, the executive chairman of the politically conservative Breitbart News, was put in charge of Donald Trump’s campaign. Now, though, mouths are foaming.

Partisan condemnation of Mr. Bannon’s recent appointment was expected. 169 House Democrats signed a letter to Mr. Trump characterizing his new appointee as a purveyor of anti-Semitism, misogyny and racism. Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid called him “a champion of white supremacy.”

In the Jewish world, the Union for Reform Judaism accused Mr. Bannon of being “responsible for the advancement of ideologies antithetical to our nation, including anti-Semitism, misogyny, racism and Islamophobia.”

The Anti-Defamation League said that Bannon is “hostile to core American values.”

Forward editor Jane Eisner, asserted that with Bannon’s appointment, “the anti-Semitic sentiments of the far right are closer to the center of political power than they have been in recent memory.”

And the National Council of Jewish Women pronounced its verdict: “Bannon and his ilk must be barred from his [Trump] administration.”

The actual evidence for labeling Bannon an anti-Semite, or enabler of anti-Semites, or racist, or all-around monster is slim. No, actually, nonexistent.

Not that a yeoman’s effort hasn’t been expended to make the case. The news organization that Mr. Bannon has headed since the death of its founder Andrew Breitbart in 2012 is certainly not to many people’s tastes (my own included). It makes famously right-leaning Fox News seem like a liberal lamb. And it has a penchant for putting provocative headlines on entirely reasonable (if arguable) opinion pieces.

Headlines like: “Bill Kristol: Republican Spoiler, Renegade Jew.” That Breitbart piece, written by political conservative David Horowitz, was an unremarkable gripe about the fact that Mr. Kristol, a dean of American conservatism, had written critically about Donald Trump. Mr. Horowitz noted how “Iran, the Muslim Brotherhood, Hezbollah, ISIS, and Hamas” have “openly sworn to exterminate the Jews,” and shared his feeling that the Obama administration was not adequately facing that threat to Jews and to America. “To weaken the only party that stands between the Jews and their annihilation, and between America and the forces intent on destroying her,” Horowitz wrote, “is a political miscalculation so great and a betrayal so profound as to not be easily forgiven.”

Whatever one might feel about that article’s thesis, it was run-of-the-mill intra-Republican kvetching and not, by any measure, anti-Semitic.

Another piece of “evidence” for Bannon’s malevolence is the claim of his former wife, in divorce documents, that, while seeking a private school for his children, he made a remark about “spoiled” Jewish children. Needless to say, unsupported (and denied) accusations in divorce proceedings deserve no one’s attention.

The strongest charge against Mr. Bannon is his statement in an interview last summer that Breitbart News is “the platform for the alt-right.”

But, as has been noted before in this space, the “alt-right” means different things to different people, and includes widely disparate elements.

What those elements generally share is a dedication to family values; a reverence for Western civilization and rejection of multiculturalism. The fringes of the movement, though, can include racism, opposition to all immigration and anti-Semitism. The fringes of the “progressive” wing of American politics, too, include Jew-haters (though they dress up their hatred as “anti-Israel” sentiment).

Imagining that Mr. Bannon meant to include the alt-right’s tattered fringes in his statement is ungenerous, and unsupported by the actual content of Breitbart offerings. As far back as 2014, he explicitly predicted that racism would eventually get “washed out” of right-wing movements.

As it happens, not only was the late Mr. Breitbart Jewish, but the news service carrying his name was started by a Jewish lawyer and businessman, Larry Solov, who conceived it during a trip he made to Israel with Mr. Breitbart. It was to be “a site,” Mr. Solov wrote, “that would be unapologetically pro-freedom and pro-Israel.” Which it has been.

I don’t automatically accept the veracity of what I read at Breitbart, or in The New York Times. Every news medium, whether it admits it or not, has its slant and partialities. A semblance of accuracy can only be gained by reading, and balancing, a variety of media, fully aware of each one’s biases.

Racism and anti-Semitism are malign, to be sure. So, though, is, carelessly and without evidence, casting labels like “racist” or “anti-Semite” about.

© Hamodia 2016

Well, we’ve all had some time by now to recover from the year-and-a-half-long national convulsion that passed for a presidential campaign. Might there be something positive to point to in an experience most of us would prefer to somehow un-experience?

Well, there’s no way to make any sort of purse, much less a silk one, out of this particular sow’s ear. But still, in the campaign’s waning days, there was a flicker of civility to behold.

It came at a time of particular tension for the Clinton campaign – after FBI chief James Comey’s first statement revealing the discovery of a new trove of possibly problematic e-mails, and before his second one revealing that the trove was untainted.

It took place at a Clinton rally at Fayetteville State University in North Carolina. As President Obama addressed the large crowd, a protester wearing a military uniform stood up at the front of the gathering, holding aloft a pro-Trump placard. Predictably, a wall of loud, sustained boos resulted.

In professorial tones, Mr. Obama told the crowd to calm down. When it didn’t, he raised his voice. “Everybody! Hey! I told you to be focused and you’re not focused right now. Sit down and be quiet for a second!” The boos faded to a muted murmur.

“You’ve got an older gentleman,” the president lectured his listeners, referring to the protester, “who is supporting his candidate. He’s not doing nothing… This is what I mean about folks not being focused. First of all, we live in a country that respects free speech. Second of all, it looks like maybe he might have served in our military and we ought to respect that. Third of all, he was elderly and we got to respect our elders.”

The incident was reminiscent of one in 2008, at a Republican town hall meeting in Minnesota, where Senator John McCain, Mr. Obama’s opponent at the time, also had to deal with supportive but misguided booing – and did so decisively.

A supporter had said he was “scared” of the prospect of an Obama presidency, and the crowd loudly vocalized its approval. But Mr. McCain refused to bask in the anger.

“I have to tell you,” he said. “Senator Obama is a decent person and a person you don’t have to be scared of as president of the United States.”

“Come on, John!” someone shouted out. Others loudly labeled Mr. Obama “liar,” and “terrorist.”

Then a woman who had been handed a microphone said “I can’t trust Obama. I have read about him and he’s not, he’s not, uh – he’s an Arab.” Mr. McCain retrieved the mike and replied: “No, ma’am. He’s a decent family man [and] citizen that I just happen to have disagreements with on fundamental issues, and that’s what this campaign’s all about.”

Such moments of comity are all too rare in the tumult of of campaign-tornados, like the recent one, that swirl angrily with snide innuendo, malign spin and outright lies – all eagerly drunk in and spat out by partisan pundits. But those moments are the ones consonant with the concept of menschlichkeit.

Pleasing, too, if not unexpected, was hearing Mrs. Clinton, the day after the election, tell her supporters that “Donald Trump is going to be our president. We owe him an open mind and the chance to lead.”

As it was hearing Mr. Obama, that same day, declaring that “we are now all rooting for [Mr. Trump’s] success in uniting and leading the country.”

The president’s decency was all the greater for his citing that of his predecessor. “Eight years ago,” Mr. Obama recalled, “President Bush and I had some pretty significant differences. But President Bush’s team could not have been more professional or more gracious in making sure we had a smooth transition so that we could hit the ground running.”

It’s no secret that I have come to judge the current president much more favorably than many in the Orthodox Jewish world. But I came to that conclusion only after Mr. Obama, to my lights, demonstrated his commitment to the safety and security of Israel and Jews. Until then, like others, I feared what the punditocracy was preaching about the purported Muslim, chassid of unhinged hater Reverend Wright, husband of a black power radical and all-around evildoer who had somehow infiltrated the White House.

Like many, even among some of Mr. Trump’s supporters, I have concerns about the president-elect. Heeding Hillary’s admonition, though, I am keeping an open mind, and will let future facts lead me where they will. I am hoping that the new president, like his predecessor, will come to pleasantly surprise me.

© Hamodia 2016

For all but the most starry-eyed devotees, or family members, of an aspirant to public service, voting essentially boils down to deciding which evil is lesser.

Well, that’s a bit harsh. What I mean is that it’s nearly impossible for any candidate to fit the full bill of any voter’s list of qualifications and preferred positions on all matters of importance. One aspirant to public office may have a preferable economic plan but a dismal approach to immigration or security matters; another may be on the right page regarding social issues but on a very wrong one when it comes to geopolitical ones. And then there are important other factors in play, like intelligence, honesty, gentility and likeability (or their absenses).

If polls and man-in-the-street interviews are any indication, in the presidential election that is rapidly (and blessedly) soon coming to an end, the “lesser evil” calculus seems particularly pertinent. Both candidates’ negative ratings are, well, impressive.

Many factors might be blamed for that state of affairs, and for the general deterioration of American political campaigning. A prominent one is money.

Hundreds of millions of dollars have been raised to feed each of the current candidates’ cash-famished campaigns. And were a dollar equivalent to be assigned to the free airtime garnered by one candidate’s propensity to make attention-getting pronouncements, he (oh, shucks, I gave it away) has effectively either paid or received the equivalent of over a billion bucks.

Most complaints about the role of money in political campaigns revolve around the undue influence wielded by a relatively small group of very wealthy individuals. And it’s a valid concern. A mere 250 donors accounted for about $44 million in contributions to the Hillary Victory Fund during the last year.

The billionaire oilman T. Boone Pickens has boasted that he “won the election in 2004 for Bush.”

In the 2012 election season, Charles and David Koch, who own the lion’s share of the second-largest privately held company in the United States, pledged $60 million to defeat Barack Obama. Of $274 million in anonymous contributions that year, according to the nonpartisan Center for Responsive Politics (CRP), at least $86 million came from “donor groups in the Koch network.”

In 1996, according to the CRP, the two major parties spent $448.9 million on the general election; in 2012, they spent $6.3 billion.

The republic’s founding fathers envisioned government as emerging from the consent of the governed, not the gvirim.

Then there is the toll taken by the fact that fundraising – in 2010, candidates for Congress spent $1.8 billion in their bids for office – has become a way of life for elected officials, swallowing up time and effort that could otherwise have been spent doing, well, what those legislators were elected to do.

Even more disturbing, at least to this decidedly apolitical observer, is what the money actually does. How, in other words, does a mega-stuffed campaign chest translate into mega-votes?

The answer is that cash can capitalize on ignorance.

Most voters, unfortunately, are far from conversant with the intricacies of issues, even those that they may care about the most. The average citizen finds calculations and thinking more than a step or two ahead to be boring endeavors, and more readily responds to appeals to emotions – good, bad and ugly ones alike.

A large chunk of political contributions goes to crafting and making those appeals. And so, political ads and mail pitches– no different in any way from those that make people buy particular brands of shampoos, beer or automobiles based on imagery and fantasy rather than quality – have become proven tools for effectively translating dollars into votes.

“Buying votes” used to mean ward bosses offering cash to individuals for their pledge to cast their ballots a certain way. Times have changed, though. Today, vote-buying is accomplished less sleazily, though no less ignobly.

In a saner democracy, there would be no campaign ads at all, only the presentation of detailed positions on issues of importance. Candidates would write manifestos, not lob accusations and insults. Debates, if we had them at all, would be strictly limited to issues, with candidates arguing the virtues of their respective goals and policies. Boasting, insulting, punching and counterpunching would be relegated to boxing rings, whence they came. (Actually, boxing is another blood sport the world would be a better place without.)

Alas, the Shafran System of Democratic Electioneering has about as much a chance at being adopted as Gary Johnson has of being elected president this November.

Still, one can fantasize, no?

© 2016 Hamodia

The image was, to be sure, jarring: Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump being draped in a tallis.

By an African-American pastor.

In a Detroit church.

To resounding applause.

Bishop Wayne Jackson of the Great Faith Ministries in Detroit effected the atifah while most of us were listening to the Krias HaTorah of Parashas Re’eh, after the candidate addressed the minister’s congregation in an attempt to garner votes from a segment of the population not naturally supportive of his candidacy.

“Let me just put this on you,” Pastor Jackson said, identifying the garment as a prayer shawl “straight from Israel,” and The Donald, although he did look a mite befuddled, didn’t resist.

The congregation was effusive in its praise of the spectacle. Some Jewish media, clergyfolk and armchair pundits, though, considerably less so.

Some took the humor route, like writer Yair Rosenberg, who speculated that “Trump was finally embracing his role as a fringe candidate.”

Others, though, were outraged at, as several described it, the “cultural misappropriation.”

One commentator called it “sacrilege” for Mr. Trump, a non-Jew, to dare to wear a “sacred garment of Jews.” Another, growing apparently increasingly apoplectic, could only comment: “The pastor just gave Trump a tallis from Israel. Which is just … no. Just no. No no no.”

Reform rabbi Ron Kronish, the founder and senior advisor for the Interreligious Coordinating Council in Israel, was appalled by the scene, which he described as “a totally absurd distortion of the meaning of an important Jewish ritual object, which is used by Jews for prayer all over the world.”

Nor could the rabbi resist the opportunity to denigrate Mr. Trump (ignoring the candidate’s karka olam passivity throughout the tallis-donning, which was unexpectedly sprung upon him by the pastor), creatively suggesting that the tallis “is a symbol of humility before G-d” and that while he “would hope that Mr. Trump would not misappropriate this ritual object for his travels… with this megalomania [sic] almost anything is possible.”

Conservative rabbi Danya Ruttenberg huffed that “A Jewish prayer shawl… is a ritual garment. Meant to be worn only by Jews. This is the worst kind of appropriation.”

And Modern Orthodox rabbi Seth Farber expressed his own great discomfort with the use of a “holy object” for “political purposes.”

Now, there is certainly something to be upset about when non-Jews utilize objects associated with Judaism to try to lure ignorant Jews away from their religious heritage. Tallisos, among other things, are routinely employed by missionaries to put a deceptive “Jewish gloss” on decidedly un-Jewish beliefs.

And the Detroit spectacle, too, in fact had distinct Christian overtones. While his victim was trapped in the tallis, Pastor Jackson offered him a second gift, two copies (one for Mrs. Trump) of something called the “Jewish Heritage Study Bible,” which includes distinctly Christian elements. The pastor also saw fit to quote from the Christian bible at that moment.

He, moreover, shared a distinctly un-Jewish description of a tallis, understanding it, apparently, as a good-luck talisman of sorts (over which, he explained, he had fasted and prayed) that, when Mr. Trump will wear it, will “lift you up.”

But the clergyman was not aiming his act or comments at Jews, but rather at Mr. Trump and the congregation. The howls of outrage, I think, say more about the howlers than about the poor pastor or the recipient of his gifts.

The misappropriation of Judaism that more merits vexation is various Jewish clergy’s abusing holy pesukim to justify some of the most decidedly un-Jewish ways of life.

We might wince at bit, or even smirk, at appropriations of things like a tallis or menorah or yarmulke (a Jewish article that most every politician, at least along the coasts, has donned on countless occasions). But waxing indignant over such sillinesses bespeaks being overly sensitive – and insufficiently appreciative of the fact that, despite the dormant, and occasionally not-so-dormant, anti-Semites that infect parts of the nation, so many Americans value, even venerate, things Jewish, and Jews.

The reverend’s reverence for the tallis and his excitement over its Israeli origin – like the blowing of shofaros at civil rights rallies or Pesach “Sedarim” at the White House – should evoke not indignation but perhaps something akin to gratitude. Gratitude, that is, for Hashem’s allowing so many of us Jews to serve out our exile-sentence today in a place where we are not only not hated and hunted but actually, in some ways, appreciated, even revered.

© Hamodia 2016

If the phrase “alt-right” puts you in mind of a computer keyboard, you are (blessedly) not following the presidential campaign.

Even if you are aware of the phrase, though, you may not have a good handle on what it means. For good reason. Many don’t. It’s a hazy phrase.

The term, which is shorthand for “alternative right,” has been in circulation for several years, but it enjoyed a recent moment in a particularly bright spotlight when presidential candidate Clinton, in a speech, sought to make a distinction between mainstream Republicans and what she characterized as holders of a “racist ideology,” i.e. the “alt-right,” who she says are a major base of support for her opponent.

The “alt-right” movement – if it can even be given a label implying some unifying philosophy – means different things to different people, as it includes disparate elements.

What those elements generally share is a dedication to family values; a reverence for Western civilization and rejection of multiculturalism; an embrace of “racialism,” the idea that different ethnicities exhibit different characteristics and are best segregated from one another; and, consonant with that latter credo, opposition to immigration, both legal and illegal.

Mrs. Clinton referenced the alt-right because her rival Donald Trump recently named a new campaign chief, Stephen Bannon, the former executive chairman of Breitbart News, a conservative website some have associated with the group.

The alt-right’s “intellectual godfather,” in many eyes, is Jared Taylor. Although he characterizes himself as a “white advocate,” he strongly rejects being labeled racist, contending that his “racialism” is “moderate and commonsensical,” a benign form of belief in the “natural” separation of races and nationalities. He contends that white people promoting their own racial interests is no different than other ethnic groups promoting theirs. He has said, “I want my grandchildren to look like my grandparents. I don’t want them to look like Anwar Sadat or Fu Manchu.”

Pointing to the homogeneity of places of worship, schools and neighborhoods, he insists that people “if left to themselves, will generally sort themselves out by race.”

Certain of Mr. Taylor’s beliefs may resonate with some Orthodox Jews. We may rightly eschew racism (seeing black Jews, for instance, no different from white ones), but we tend to be less than enamored of some elements of various minority cultures; we deeply value ethnic cohesion, preferring to live in neighborhoods among “our own kind”; and we have serious problems with certain elements of “progressive” western civilization and multiculturalism.

Mr. Taylor, in fact, welcomes Jews. He has said that we “look white to him.”

That sentiment though, is not typical among others under the alt-right umbrella.

Even a nuanced rejection of non-western cultures inevitably attracts genuine racists and haters, and devolves into rejection of the eternal “other”: Jews. The American far right has always embraced, inter alia, one or another form of Jew-hatred. More balanced members of the alt-right refer to their “1488ers” – a reference to two well-known neo-Nazi slogans, the “14 Words” in the sentence “We Must Secure The Existence Of Our People And A Future For White Children”; and the number 88, referring to “H,” the eighth letter of the alphabet, doubled and coding for “Heil Hitler.”

And even Mr. Taylor has permitted people like Don Black, a former Klan leader who runs the neo-Nazi Stormfront.org web forum, to attend his conferences. He may or may not endorse Black’s every attitude, but neither has he rejected his support.

Back in the 1960s, the John Birch Society, then dedicated to the theory that the U.S. government was controlled by communists, was condemned by the ADL for contributing to anti-Semitism and selling anti-Semitic literature. The brilliant and erudite William F. Buckley Jr., the unarguable conscience of conservatism at the time, recognized the group’s nature, and the threat its extremism posed to responsible social conservatives. In the magazine he founded, National Review, he denounced and distanced himself from the Birchers in no uncertain terms, contending that “love of truth and country call[s] for the firm rejection” of the group.

It is ironic that it has fallen to the Democratic presidential contender to make a distinction between responsible Republicanism and the current loose confederacy that includes haters.

In the wake of Buckley’s denunciation of the alt-righters of the time, some National Review subscribers angrily cancelled their subscriptions. Others, though, were appreciative of Buckley’s stance. One wrote: “You have once again given a voice to the conscience of conservatism.”

That letter was signed “Ronald Reagan.”

© 2016 Hamodia

What’s omitted from a discussion can sometimes speak quite loudly. And sometimes quite disturbingly. That’s true, I think, about the national conversation about the Khizr and Ghazala Khan/Donald Trump contretemps.

Unless you’ve been summering in the Australian outback and off the grid, you likely know that the most memorable moment of the Democratic National Convention (at least if the idea of a woman presidential nominee somehow didn’t make you swoon) was the speech delivered by the aforementioned Khizr Khan, a Pakistani-born, Harvard Law School-educated American citizen. Mr. Khan has worked in immigration and trade law, and founded a pro bono project to provide legal services for the families of soldiers. The Khans’ son, Humayun, an Army captain, was killed in 2004 while protecting his unit.

At the convention, Mr. Khan identified himself and his wife, who stood at his side, as “patriotic American Muslims,” and sharply condemned Donald Trump for what the Khans see as his bias against Muslims and divisive rhetoric. “You have sacrificed nothing,” he added, addressing Mr. Trump, “and no one.”

Mr. Trump, in subsequent interviews, responded to that accusation by arguing that he had raised money for veterans, created “tens of thousands of jobs, built great structures [and] had tremendous success.” And he also speculated that the reason Mrs. Khan hadn’t spoken was because, as a Muslim, “maybe she wasn’t allowed to have anything to say. You tell me.”

Mrs. Khan explained her reticence in a Washington Post essay. “Walking onto the convention stage, with a huge picture of my son behind me,” she wrote, “I could hardly control myself. What mother could?”

The punditsphere went wild, mostly with applause for the Khans and derision for Mr. Trump. There were the expected right-wing “exposés” of the Khans’ (nonexistent) connections to terrorist organizations, but the responsible responses to the showdown were critical of the Republican candidate and sympathetic to the Gold Star parents.

But while there is no reason to doubt Mrs. Khan’s claim that she was just too anguished by the memory of her son to speak, something that should have been considered somewhere in all the seeming millions of words that were produced on the row simply wasn’t.

That would be the possibility that a woman might choose, for religious reasons, to not avail herself of center stage and a microphone. All sides of the controversy seem to have agreed to the postulate that tznius is a sign of backwardness, or worse.

That was unarguably the upshot of Mr. Trump’s infelicitous insinuation, that Mrs. Khan’s silence at the convention was religious in nature, and evidence that Islam is intolerant and repressive.

To be sure, there are sizable parts of the Islamic world where women are in fact cruelly oppressed, where physical abuse, forced marriages and “honor killings” are unremarkable. But what Mr. Trump was demeaning was the very concept of different roles for men and for women, the thought that a woman might, as a matter of moral principle, wish to avoid being the focus of a public gathering. He was insinuating, in other words, that a traditional idea of modesty is somehow sinister.

Islam, though some Muslims may chafe at the observation, borrowed many attitudes and observances from the Jewish mesorah. Islam’s monotheism and avoidance of graven images, its insistence on circumcision, its requirement for prayer with a quorum and facing a particular direction, its practice of fasting, all point to the religion’s founder’s familiarity with the Jews of his time. As does that faith’s concept of tznius, even if, like some of its other borrowings, it might have been taken to an unnecessarily extreme level.

I don’t know the Khans’ level of Islamic observance, but Mrs. Khan wore a hijab as she stood next to her husband at the convention podium. So it is certainly plausible that her decision to not speak in that very public venue may have been, at least to a degree, informed by a tznius concern.

A concern that the plethora of pundits chose to not even consider, thereby, in effect, endorsing Mr. Trump’s bias on the matter.

To be sure, and most unfortunately, tznius isn’t an idea that garners much respect in contemporary western society. Moreover, Mr. Trump’s relationship with any sort of modesty is famously fraught.

But it is particularly disturbing that his insinuation that traditional roles for men and women bespeak repression and backwardness went missing in the national discussion, altogether unchallenged by the ostensibly open-minded men and women of the media.

© 2016 Hamodia

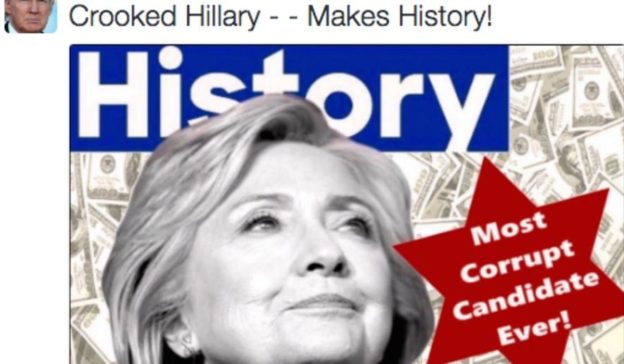

“The anti-Semitism that is threaded throughout the Republican Party of late goes straight to the feet of Donald Trump.” That, according to Florida Congresswoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz, then-chair of the Democratic National Committee. Mr. Trump, she added, has “clearly demonstrated” anti-Semitism “throughout his candidacy.”

Evidence proffered for the Republican nominee’s alleged Jew-hatred includes the now-famous image disseminated by the Trump campaign, which depicted Hillary Clinton accompanied by mounds of money and a six-pointed star. The image, it turned out, had been borrowed from a white supremacist website.

Then there is the candidate’s speech to a group of Republican Jewish donors in which he said that he didn’t want their money (a sentiment that drew praise from Louis Farrakhan, not otherwise a Trump supporter). And the fact that Mr. Trump has been endorsed by people like David Duke.

More recently, when a Jewish former Governor of Hawaii, Linda Lingle, spoke at the Republican national convention, a torrent of anti-Semitic comments spilled onto the comments section of a livestream of the event. They included praise for Hitler, ym”s, images of yellow stars accompanying the epithet “Make America Jewish Again” and comments like “Ban Jews.”

One needn’t be a supporter of Mr. Trump, though, to recognize that the anti-Semitism charges against him are seriously, forgive me, trumped up. In fact, they’re nonsense.

That he has an Orthodox-converted Jewish daughter and a Jewish son-in-law (and three grandchildren, whom he often refers to as his Jewish progeny), with all of whom he is close, should itself be enough to put the charge to rest.

If more is needed though, well, the Trump Organization’s longtime chief financial officer, Steve Mnuchin, and general counsel, Jason Greenblatt, are both observant Jews. The latter, who has worked for Trump since the mid-1990s, is one of the candidate’s top advisers on Israel and Jewish affairs. And another top Trump adviser has said that Trump backs an Israeli annexation of all or parts of the West Bank. The candidate once received an award from the Jewish National Fund and served as grand marshal of the New York Israel Day parade.

I’m not sure what David Duke or Louis Farrakhan make of all that, but such people, in any event, don’t traffic in facts.

I remind readers that not only does Agudath Israel of America not endorse or publicly support candidates, neither do I as an individual – the role in which I write this column. I am concerned only with what I perceive to be truth and fairness.

Mr. Trump cannot be blamed, either, for support he has received from unsavory corners. He may or may not be happy with haters’ support (politics, after all, being, above all else, about votes). But he has clearly disavowed the sentiments of Duke and company, and can’t be expected to respond each time a malignant mind embraces his candidacy.

Depending on one’s own personal constitution, Mr. Trump may seem refreshing or revolting; his policies, sensible or seditious; his demeanor, exhilarating or unbalanced. But his alleged anti-Semitism is unworthy of anyone’s consideration.

What is, though, worth noting is the aforementioned malevolence, the packs of dogs who hear and respond to imaginary Jew-hate whistles.

As we go about our daily lives, unburdened by the angst and terror that were part of our forbears’ lives over millennia in other lands, it’s easy to imagine that the land of the free is free, too, of Jew-hatred. Then come times, like the current one, when our bubble is burst.

Bethany Mandel is a young, politically conservative, Jewish writer. After she penned criticism of Mr. Trump, a tsunami of spleen spilled forth.

Among what she estimates to be thousands of anti-Semitic messages aimed at her were suggestions like “Die, you deserve to be in an oven,” and depictions of her face superimposed on the body of a Holocaust victim.

“By pushing this into the media, the Jews bring to the public the fact that yes, the majority of Hilary’s [sic] donors are filthy Jew terrorists,” wrote Andrew Anglin in the Daily Stormer, a site named in honor of the notorious tabloid published by Nazi propagandist Julius Streicher, ym”s.

Though it’s disconcerting to perceive, beneath the verdant surface of our fruited plain, some truly foul and slimy things, it’s important, even spiritually healthy, to do so.

Because, amid our protection and our plenty, we are wont to forget that we remain in galus. And that’s a thought we need to think about, especially, the “three weeks” having arrived, this time of Jewish year.

© 2016 Hamodia

With the Democratic and Republican platforms offering more polarized planks on abortion than ever, the issue of “reproductive rights” is, once again, well, birthed into the glare.

Also in the limelight of late are some misleading assertions about Judaism’s attitude toward fetal life.

An op-ed of mine on the topic in Haaretz is here.

Or, to receive a copy of the piece, just request one, from rabbiavishafran42@gmail.com .

So, where exactly was the lie?

The one, that is, to which the meraglim had to add some truth, in order for it to be swallowed.

In this past Shabbos’ parashah, the spies, returning from Kenaan, reported to Moshe Rabbeinu that they “came to the land to which you sent us, and indeed it is flowing with milk and honey” (Bamidbar, 13:27). Quoting the Gemara (Sotah, 35a), Rashi comments that “Any lie in which a little truth is not stated at the start cannot be maintained in the end.”

But not only was the report of the land’s bounty true. So was, at least on the surface, everything else the meraglim reported. Yes, they described the fearsome inhabitants of the land, the “men of stature,” and the burials of many of the land’s inhabitants. That negativity constituted dibah, as the Torah itself says – as Chazal put it, lashon hara. But where was the untruth, the lie?

Rav Yaakov Moshe Charlop, z”l, in his sefer Mei Marom on Chumash, suggests an answer.

The Midrash Tanchuma, brought by Rashi on the words “hechazak hu harafeh” (“Are they strong or weak?”) says that Moshe gave the meraglim a sign: “If they live in open cities [it is a sign that] they are strong, since they rely on their might. And if they live in fortified cities [it is a sign that] they are weak.” (ibid,13:18)

And yet, notes Rav Charlop, the spies reported that “the people who inhabit the land are mighty, and the cities are very greatly fortified” (3:28). A self-contradiction, since if the inhabitants were indeed mighty, as per Moshe’s sign, they would not have needed to fortify their cities. And if their cities were fortified, that meant the people were feeble. There, the Mei Marom suggests, lies the lie.

That walls are antithetical to strength is a thought worthy of consideration in contemporary times, here in the U.S.

Fortifying our country against infiltrators bent on harming us, or on changing the nature of the republic, has been a major topic of discussion in the presidential campaign over many months – indeed, in the national marketplace of ideas for much longer.

President Obama recently asserted that “America is a nation of immigrants. That’s our strength. Unless you are a Native American, somebody, somewhere in your past showed up from someplace else, and they didn’t always have papers.” That’s a truth that we Jews know well.

But concern about how to deal with the estimated 3.6 million undocumented immigrants currently in the country is valid, too. As is – even more so – concern about the possible leanings of some who wish to come to America.

Regarding the former, a deadlocked Supreme Court recently quashed any chance of resolving the issue before the presidential election, leaving in place an injunction blocking the president’s “Deferred Action for Parents of Americans” plan (DAPA), deferring deportations of undocumented immigrants who have American families and no criminal record, and allowing them to obtain work permits.

Hillary Clinton has pledged, if elected, to continue to push for DAPA, presumably after nominating a replacement to the late Antonin Scalia’s High Court seat. Donald Trump has called DAPA “one of the most unconstitutional actions ever undertaken by a president” and has said he’d deport all undocumented immigrants.

He has also seized the issue of the threat posed by future immigration, promising to ban all Muslims from coming to the U.S.

Immigration is one of those issues (are there really any others these days?) about which many get hot and polarized, righteously glomming onto one extreme position – that we should open our borders to any and all, and relax quotas and scrutiny – or the other – that we should deport all undocumented immigrants and accept no Muslims.

The wisest approach, though, as so often it does, likely lies someplace in the middle here, with reasonable accommodation of, but clear demands on, foreigners already living in the U.S. for years; and intensified scrutiny of new immigrants – based on region of origin, not religion.

But whatever one’s position on immigration issues, the midrash’s words speak to us. Should America in fact need to build physically high border walls and conceptually high barriers to immigration, what it will reveal, according to the formula conveyed by Moshe Rabbeinu to the meraglim, is not how strong our nation is, but the opposite.

Walling off America, in other words, is the converse of making it great.

© 2016 Hamodia