As is the case with any question about nature, when a child asks why the sky is blue, the answer one gives (here, that blue light is scattered more than other colors) will elicit a subsequent question of why (because it travels as shorter, smaller waves). And then that answer, in turn, will yield yet another question: Why is that? Eventually, the final answer will always be: “That’s just the way it is!” In other words, it’s Hashem’s will.

Rav Dessler famously explained that every aspect of nature is no less a miracle than a sea splitting, an act of G-d. What we choose to call miraculous is just a divine-directed happening we’re not used to seeing.

The most fundamental element of nature, arguably, is time. The past, from our perspective, is past, and time proceeds relentlessly into the future. But time, too, is a divine creation. Commenting on the Torah’s first words, which introduce Hashem’s creation, “In the beginning…,” the Seforno writes: “[the beginning] of time, the first, indivisible, moment.”

Time is the bane of human existence. The Kli Yakar notes that the word the Torah uses for the sun and moon—“me’oros,” or “luminaries” (Bereishis, 1:16), which lacks the expected vov, can be read “me’eiros,” or “afflictions.”

“For all that comes under the influence of time,” he explains, “is afflicted with pain.”

Rabbi Yitzchak Hutner, zt”l, notes, similarly, that the term “memsheles” (ibid), which describes those luminaries’ roles, implies “subjugation.” For, the Rosh Yeshiva explains, we are enslaved by time, unable to control it or escape its relentless progression. Our positions in space are subject to our manipulation. Not so our positions in time.

But time,, like the rest of nature, can be manipulated, of course, by Hashem’s will. Indeed, as it happens, astoundingly, it can be manipulated by our own as well.

In Nitzavim, which is always read before Rosh Hashana, are the words: “And you will return to Hashem…” (Devarim 30:2).

Teshuvah, Chazal teach us, can change past intentional sins into unintended ones. Even, if the teshuvah is propelled by love of Hashem, into merits (Yoma 86b). Quite a remarkable thought. Chilul Shabbos transformed into reciting kiddush on Shabbos? Eating treif into eating matzah on Pesach? Telling lashon hora into saying a dvar Torah?

By truly confronting our past wrong actions and feeling pain for them, and resolving to not repeat them, we can reach back into the past and actually change it. We are freed from the subjugation of time. Is that not the temporal equivalent of the splitting of a sea?

Which thought might well lie at the root of the larger theme of freedom that is so prominent on Rosh Hashana. Tishrei, the month of repentence, is rooted in “shara,” the Aramaic word for “freeing”; the shofar is associated with Yovel, when servants are released; we read from the Torah about Yitzchak Avinu’s release from his “binding”; and Rosh Hashanah is the anniversary of Yosef’s release from his Egyptian prison, and of the breaking of what can be thought of as Sarah and Chana’s childlessness-chains.

And that ability to manipulate time may be why, on Rosh Hashanah, unlike on every other Jewish yomtov, the moon, the “clock” by which we count the calender months of the year, is not visible. The moon is, famously, a symbol of Klal Yisrael. It receives its light from the sun, just as we receive our enlightenment, and our mission, from Hashem; it wanes but waxes again, as Klal Yisrael does throughout history.

The subtle message in the moon’s Rosh Hashana invisibility may be the idea that time need not limit us, if we successfully engage the charge of the season. We are guided to imagine that the sky, with its missing “Jewish clock,” is reminding us, at the advent of the Aseres Yimei Teshuva, that time can be overcome in an entirely real way, through the Divine gift of teshuvah, powered by our heartfelt determination.

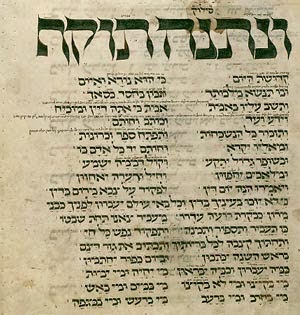

Ksivah vachasimah tovah!