Ami Magazine received a good number of letters about a column I wrote about the Ottawa trucker protest, wherein I noted some concerning elements that were part of it. The magazine wanted to publish three of them and I offered a response. In the end, due to space considerations, only one letter was published, the following one, which, here, is followed in turn with my response:

Dear Editor:

A few weeks ago, Rabbi Shafran wrote an article discussing the fact that it is inappropriate to determine a true impartial conservative standpoint on anything political lest the opposing side’s argument is hearkened and comprehensively reviewed. It is a very rational perspective I totally agreed with. But lately I have gotten the impression that Rabbi Shafran has taken it too far. His views have moved ever more to the left and it almost seems as if he’s grown a bias against the right wing, versus impartiality.

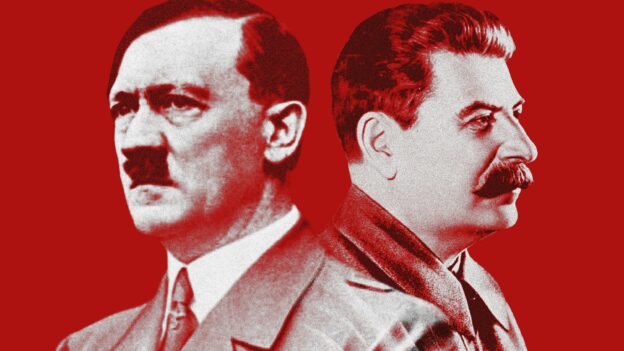

There were, for example, his take on the radical steps taken by the AG against vocal parents and his smearing of only Republican politicians who used Holocaust analogies, while ignoring the long list of Democrats doing the same. So I wasn’t surprised at last week’s article condemning the massive truck protest in Canada, though I did think some disagreement was warranted.

The unconstitutionality of these draconian vaccine mandates and those who raise the fact that it is illegal are dissociated, and the fact that James Bauder believes in some conspiracy theories doesn’t make his argument any less compelling. The right to protest on the other hand, however big a disruption to people’s lives or to commerce, is an elementary right in every democratic country.

Yet in this article, it is somehow deemed more disquieting than a breach of the most basic of freedoms; being coerced via unconstitutional mandates and taxations to jab a widely speculated vaccine (however illogical the speculation) into one’s own body. The article also mentions how the word “freedom” has morphed “from when it meant the desire of slaves to live normal lives to… the refusal to help stem the spread of a disease.”

So, needless to say, the dictionary was created long before this topic came up and actually defined the word “freedom” as the power to act, think or speak without hindrance and restraint. Only the left gets so stuck on slavery and racism with regard to anything and everything.

Now, the response Canada has taken is heavily outrageous. It definitely won’t help, for these protesters are so driven against vaccines that they’re ready to lose their job, getting arrested probably won’t deter them either. But there is a large-scale difference between being arrested for clogging up the traffic purposefully in Ottawa, even the minority protesting with hateful slogans, and those committing acts of violence. And that’s not happening here.

The kind of language and activity that has now been invoked by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in Canada, is actual tyranny. The use of the Emergency Act in order to clear protesters off the streets, is something that in the United States would receive heavy consternation on a major-scale. When Senator Tom Cotton wrote an op-ed in the New York Times suggesting that rioters be cleared off the streets via the use of the US military if need be, the entire left went so insane that the op-ed editor for the paper was fired for the crime of having printed that op-ed. And he was talking about rioters, he wasn’t talking about protesters, he wasn’t talking about people marching peacefully on the street, yet he was so strongly censured.

Moshe U.

Los Angeles, CA

Response

Dear Reb Moshe,

First and foremost, thank you for sharing your perspective. I write to stimulate thought; and responses, positive or otherwise, indicate I’ve been successful.

To some of your points:

I am neither on the “left” nor on the “right.” I’m not into clubs and I eschew groupthink, the yield of partisanship. I engage topics by reading varied viewpoints, doing rigorous fact checking and formulating my own opinion. You can find very “conservative” articles of mine on issues like assisted suicide and public school prayer at Fox Opinion; similar ones about moral issues and feminism in Forward; and about discriminatory Covid restrictions at NBC-THINK. But I don’t automatically endorse what any political party or philosophy may embrace.

If my research on any particular issue leads me to a different conclusion from others’, well, that means that… I have a different opinion. Please don’t shoot.

The “draconian vaccine mandates” in Canada are neither draconian nor, precisely speaking, mandates. Nor have Canadians been “coerced” or been subjected to “egregious human rights violations.” Our neighbor to the north has not held Canadians down and vaccinated them against their will, which would arguably be a violation of their rights. It has simply extended a border-crossing vaccine requirement to include truckers, who most certainly do interact with other people during their runs, deliveries and pick-ups. That is not a curtailment of freedom, but a responsibility placed on citizens intended to protect others. One might well feel that the new rule was unnecessary or even objectionable. But one might feel otherwise, too. There can be, and often are, two different reasonable positions on a topic.

There is indeed a right to protest in Canada, as in our country. But all rights have limits. Police in both countries routinely move demonstrators, even with force, when they become disruptive of others’ rights. And Canada waited several weeks, during which Ottawans endured noise and the inability to get around, before obtaining a judge’s approval, warning the truckers to disband and only then clearing them out.

If my invocation of slavery in America to illustrate the morphing of the word “freedom” as it is used politically these divisive days was somehow offensive, let me replace that example with the freedom Hashem granted Klal Yisrael from their shibud in Mitzrayim. Contrast that oppression with the plight of the truckers.

And speaking of racism, a useful thought experiment would consist of our imagining that the Canadian truck protest was about (real or perceived) mistreatment of African-Canadians, and sponsored by a BLM group. Would you champion a weeks-long disruption of lives and commerce, and be so outraged at someone who pointed out the disturbing record of the organizers, or the ugly actions of some of the demonstrators? If so, then at least you’re consistent. If not, well, then… you’re not.

Mr. Trudeau’s invoking of the emergency powers act, later endorsed and extended by the Canadian House of Commons, took place after my column was submitted for publication. I didn’t find it egregious, though, and, incidentally, I felt the same way about Mr. Cotton’s suggestion, and felt that the criticism of him was wrong.

The reason I wrote my column was just to point out some disconcerting facts about some of the protesters and one of their officials that I felt were likely unknown to readers.

Some others:

• Aside from the Nazi flag and multiple Confederate and QAnon ones, and from the protester who danced on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, others desecrated the statue of celebrated cancer research activist Terry Fox with political and anti-vaccine signs; and others urinated on the National War Memorial. Signs with angry obscenities abounded. Numerous photos and videos show the less-than-“heartfelt and touching” signs.

• Polling firm Innovative Research Group found (in a survey from Feb. 4-9) that a mere 29 percent of Canadians expressed support for “the idea of the protest” while 53 percent disapproved. A separate survey by Léger, released on February 8, found that 62 percent of Canadians oppose “the message that the trucker convoy protests are conveying of no vaccine mandates and less public health measures.”

• Ontario’s Special Investigations Unit, a police watchdog, is investigating two injuries among the thousands of protesters, both having occurred after a crowd refused to disperse. Only one injury was serious, that of a 49-year-old (not, as another letter writer claimed, a83-year-old) woman, and it has not yet been determined whether a horse struck her or she was knocked down by other protesters amid the commotion. No one was (as the letter writer claimed) “trampled.”

• 13 people connected to the trucker protest in Alberta were found with more than a dozen long guns, hand guns, ammunition and body armor.

Again, my thanks for sharing a different perspective, which, even in disagreement, I fully respect. I can only ask that you give the same consideration to my perspective, and the facts I have offered in its support. And that you accept my sincere assertion that I stand not on “the left” nor on “the right,” but rather where the facts and my best shot at objective judgment take me.