An article in Haaretz rebutting an earlier one there that mischaracterized the recent Supreme Court decision about inequitable restrictions on houses of worship in New York can be read here.

An article in Haaretz rebutting an earlier one there that mischaracterized the recent Supreme Court decision about inequitable restrictions on houses of worship in New York can be read here.

This article appears at the Forward this morning and can be read here.

Yaakov famously sequestered Dinah his daughter in a box as he prepared to meet Esav his brother.

That, according to the Midrash Rabbah brought by Rashi (Beraishis 32:23). His reason for hiding Dinah, the Midrash notes, was because he feared that Esav would, upon seeing her, wish to marry her. And he didn’t want to take that chance.

But there’s a phrase in the Midrash, though, that is easily overlooked. Not only did he put his daughter in a box, he “locked her in.”

What that seems to indicate is that Yaakov knew that, as Chazal explain at the very beginning of the saga of Dinah’s abduction and rape by Shechem, she was a yatzanis, an “outgoing personality.” She was a naturally curious person. And so, prudently, her father locked her in, since he feared she might emerge during his meeting with Esav to witness the goings-on.

And, according to the Midrash, Yaakov is faulted for that, since, had Dinah in fact been seen by Esav and ended up marrying him, she might have been able to turn his life around and alter the enmity he held in his heart for Yaakov.

But wasn’t Yaakov right to do what he did?

Apparently not. The question is why.

What occurs is that children have natural proclivities and tendencies. There are times, to be sure, indeed many times, when a child has to receive “no” as an answer.

But squelching a child’s nature is not a good idea. It can easily backfire. Ideal child rearing is channeling the child’s nature, not seeking to squelch it. (See Malbim on Chanoch lina’ar al pi darko (Mishlei 22:6).

My wife and I know a couple whose little boy seemed obsessed with airplanes, beyond the normal interest in such things of all little boys. The parents didn’t try to dissuade him from his desire, as he grew, to fly or work with planes, to force him, so to speak, into a box. They allowed him to express it, and the little boy is grown today, a yeshiva (and flight school) graduate who is a certified air traffic controller, and he’s raising a beautiful, Torah-centered family with his wife, our daughter.

© 2020 Rabbi Avi Shafran

The recent charging of a nurse in England with the murder of eight babies in a hospital’s neonatal unit prodded me to write last week’s Ami Magazine column about similar crimes, government-sanctioned assisted suicide and the common condition I call “23-Pair Chromosome Syndrome.”

The column can be read here.

Some people’s default attitude in life is “I really deserve more than I have”; others are prone to feeling that “I really don’t deserve what I have.”

Most people fall somewhere on the spectrum between those two extremes, and most people also may experience one of the attitudes at some points, the other at others.

Menachem Mendel of Kotzk, the Kotzker Rebbe, pointed out that, even though Jews are descended from 12 tribes, the sons of Yaakov, we are called Jews (Yehudim, in Hebrew), after only one of those progenitors, Yehudah, or Judah.

That, he contended, is because Jews are meant to embody the sentiment that yielded Yehudah his name — his mother Leah’s declaration at his birth that she was the beneficiary of what she “didn’t deserve.”

Since Yaakov had children from four women and Leah knew her husband was destined to father 12 sons, she expected to bear only three. Yehudah was her fourth. And she acknowledged (“odeh,” the root of “Yehudah”) the fact that she had “received more than my share” (Beraishis 29:35; see Rashi).

Traditionally, the first words to leave a Jew’s mouth each morning upon awakening are “Modeh Ani” (or, for a woman, “Modah Ani”) — “I acknowledge.” The acknowledgment is for having woken up, for life itself. A Jew is meant to take nothing for granted, to take everything he has as a divine gift.

Yaakov’s middah is emes, truth, and so Rashi parses Yaakov’s misleading words to Yitzchak to make them true at least on some level. For instance, allowing his father to believe it is Esav to whom he is speaking, Yaakov says “I am Esav your firstborn.” Rashi interjects a presumed pause in the sentence, rendering it “I am [the one bringing you food]; Esav is your firstborn” (Braishis, 27:19).

Yet one misleading phrase still stands out: “Come eat of my hunted [food]” (ibid), says Yaakov, offering his father the goat meat he could mistake for game. But it was neither Yaakov’s food – his mother Rivka had prepared it – nor had it been “hunted.”

What occurs is that “hunting” is a word we’ve seen earlier, as the Torah’s description of Nimrod, “a powerful hunter” (ibid 10:9). And there, Rashi explains that what Nimrod “hunted” and captured were people’s minds. He used words and subterfuge to amass followers.

Perhaps here, too, Yaakov was subtly, slyly “confessing” to his father that he was engaged in a subterfuge, presenting himself as someone he wasn’t, offering his “hunting” to Yitzchak, his ability to navigate a tricky world. Thereby demonstrating that he, Yaakov, too, was capable of dealing with that challenging world no less than his brother, something that, as the Malbim and others explain, Yitzchak had assumed was not true.

It’s human nature, when faced with something tragic, or even just disturbing, to say to oneself, “If only…”

“If only I had done this… or we had done that… or not done this… or not done that, we could have avoided this outcome.”

But human nature can be misleading. A thought I once heard from someone who couldn’t remember its source suggests that the repetition of the phrase, “the years of Sarah’s life,” in the first pasuk of the parsha, even though the pasuk opened with “And the lifetime of Sarah was 127 years,” teaches us to resist our proclivity to imagine that things could have been different had we only acted differently.

To be sure, there are rightful regrets that we may have. Someone grown obese and unhealthy after overeating junk food for years has good reason to say, “if only.”

But more often than not, post-facto calculi are wrongheaded. We might think that had Sarah not been told (as per a famous Midrash) about her son having been bound on an altar, she wouldn’t have died at the moment she did, having been spared the shock.

But Sarah’s death was divinely ordained for that moment. “The years of Sarah’s life” were the years granted her. The proximate cause of her death wasn’t its ultimate cause. Its ultimate cause was Hashem’s will.

Someone who comes down with Covid-19 might kick himself for having worn only a simple mask, not an expensive, surgical-quality one. Or for having spaced himself only 6 feet from others, instead of 10. We are required to do what is normative practice to prevent sickness — but only that. And if one had done that and still became sick, he is wrong to agonize over not having done more. He needs to recognize Hashem’s will and now do what is normative practice to, with Hashem’s help, recover.

Recent columns of mine that have appeared in Ami Magazine can be accessed through the links below:

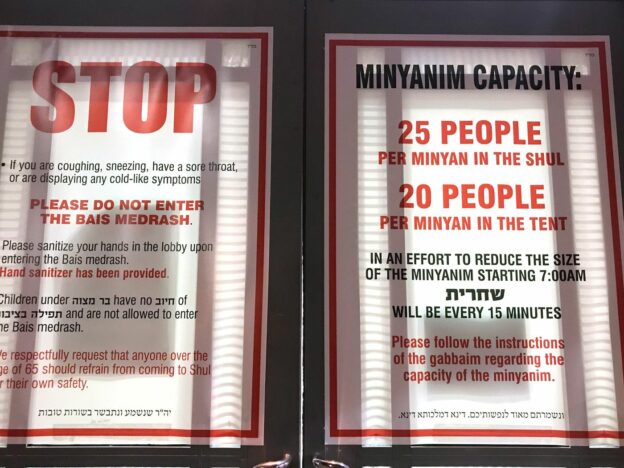

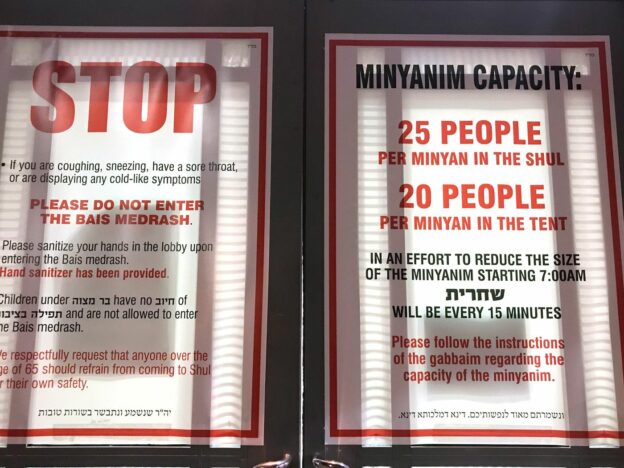

An article I wrote for Religion News Service about what New York’s draconian Covid-19 rules affecting Orthodox communities evidence about the rules’ crafters can be read here.

Remarkably, in response to Avimelech’s protest over being punished for taking Sarah, Hashem confirms the king’s insistence that he had acted innocently, believing that Avraham and Sarah, as they had claimed, were brother and sister.

“I, too, knew,” Hashem tells Avimelech in a dream, “that it was in the innocence of your heart that you did this” (Beraishis, 20:6).

So why didn’t Hashem merely prevent Avimelech from touching Sarah? Why were the king and his family and entourage punished?

Perhaps the answer lies in what Avraham told Avimelech in explanation for having misled him: “Because I said ‘There is no fear of G-d in this place’ ” (ibid, 11).

A leader has the ability, and responsibility, to influence the mores of his society. If the society evidences lack of “fear of G-d,” its leadership is implicated.