Much of the “pro-Palestinian” (read: anti-Israel—and, more often than not, anti-Jew) activism has been angry, crass, disruptive and destructive.

And, at least in one recent case, counterproductive.

To read about it, click here.

Much of the “pro-Palestinian” (read: anti-Israel—and, more often than not, anti-Jew) activism has been angry, crass, disruptive and destructive.

And, at least in one recent case, counterproductive.

To read about it, click here.

It’s easy to resent being mistreated.

It’s also misguided to be resentful.

Yosef reassures his brothers that he harbors no ill will for their having plotted against him. “Although you intended me harm, Elokim intended it for good” (Beraishis 50:20), he tells his siblings, echoing his earlier words “It wasn’t you who sent me here, but rather Elokim (ibid 45:8).

Those statements, Rav Yeruchom Levovitz, the famed Mir mashgiach, explained, were not mere polite, comforting words of forgiveness. They meant precisely what they say: that Hashem was ultimately the reason for his having been mistreated and sold into servitude. [Note the use of “Elokim” in both psukim, indicating din, pure justice]. It was part of a plan.

In his Daas Torah, Rav Yeruchom writes that Yosef was telling his brothers that they really had nothing to do with his life’s trajectory, that they had essentially been mere tools that were used in order to bring him to who he had become, the viceroy of Mitzrayim.

And so, Rav Levovitz continues, every person who feels wronged by another should not automatically be angry at his oppressor, since he is where Hashem wants him to be. Would anyone, the mashgiach asks, think to rail against a stone that fell on him? The oppressor is but a stone, the means by which Hashem’s plan for the injured person is furthered.

It’s an attitude vital for living a Torah-informed life.

“Take this rule,” says Rav Yeruchom, “firmly in hand.”

© 2025 Rabbi Avi Shafran

What do you think represents an “egregious threat to bedrock principles of academic freedom”?

The kidnapping and gagging of a professor? An administrator’s cancellation of the professor’s class? . A warning that he’d be fired unless he taught a certain point of view? Three strikes, you’re out.

To see the answer, click here.

Shepherds were abhorrent to ancient Egyptians, Yosef tells his brothers, as he relates what they should tell Par’oh in order to reserve the area of Goshen for his immigrating family (Beraishis 46:34). We find this in Mikeitz as well (43:32; see Rashi and Onkelos there)

Some commentaries understand that as indicating that the Egyptians protected livestock and shunned the consumption of meat. Ibn Ezra writes that the Egyptians were “like the people of India today, who don’t consume anything that comes from a sensile animal.”

Pardes Yosef (Rabbi Yosef Patzanovski) references the Ibn Ezra and explains that the ancient Egyptians considered the slaughter of an animal to be equivalent to the murder of a human being.

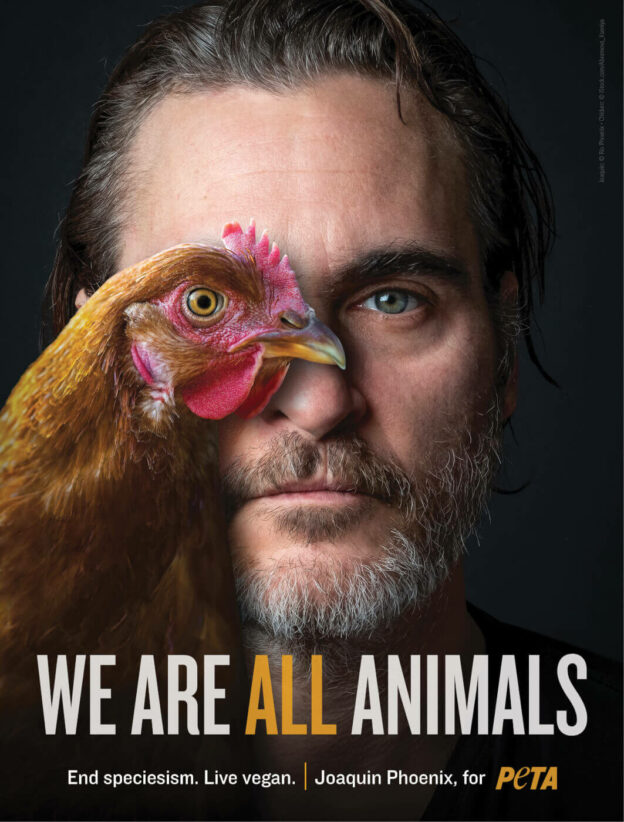

Although far distant in both time and place from ancient Egypt and India, some people in the Western Hemisphere today have come to embrace the notion that the sentience of animals renders them essentially no different from humans.

To be sure, seeking to prevent needless pain to non-human creatures is entirely in keeping with the Jewish mesorah, the source of enlightened society’s moral code. But those activists’ convictions go far beyond protecting animals from pain; they seek to muddle the fundamental distinction between the animal world and the human. A distinction that is all too important in our day, for instance, when it comes to issues pertinent to the beginning or end of life, or moral behavior.

A book that focuses on “the exploitation and slaughter of animals” compares animal farming to Nazi concentration camps. Its obscene title: “Eternal Treblinka.” Similarly obscene was the lament by People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals founder Ingrid Newkirk that “Six million Jews died in concentration camps, but six billion broiler chickens will die this year in slaughterhouses.”

But even average citizens today can slip onto the human-animal equivalency slope. American households with pets spend more than $60 billion on their care each year. People give dogs birthday presents and have their portraits taken. Such things might seem benign but, according to one study, many Americans grow more concerned when they see a dog in pain than when they see an adult human suffering.

We who have been gifted with the Torah, as well as all people who are the product of societies influenced by Torah truths, consider the difference between animals and human beings to be sacrosanct.

It is incumbent on us to try to keep larger society from blurring that distinction.

© 2024 Rabbi Avi Shafran

The Catholic Church as an institution has come a long way with regard to its attitude toward the Jewish people. But, apparently, it still has, as they say, a ways to go.

You can read what I mean here:

“Why display yourselves when you are satiated, before the children of Esav and Yishmael?” (Rashi, Beraishis 42:1).

That is the Gemara’s (Taanis 10b) understanding of Yaakov Avinu’s exhortation to his sons, lama tisra’u (understood, apparently, as “why be conspicuous?”). His rhetorical question was posed to ensure that “they will [the children of Esav and Yishmael] will not be jealous of you….” as they journey to Mitzrayim to garner food during the famine.

Chazal say that, in general, “a person should not indulge in luxury” [ibid]. But especially when it might generate jealousy and resultant animosity.

It is a lesson for the ages, and needed throughout the ages. Among others, the Kli Yakar, who died in 1619, lamented the fact that some Jews’ homes and possessions in his time proclaimed their material success. The problem has hardly disappeared today.

(One of the things that attracted me to the community where I live was the basic uniformity of the homes there. There are no mansions here, not even McMansions.)

Several commentaries wonder at the Gemara’s reference, in the opening quote above, to the progeny of Esav and Yishmael. Yaakov was in Cna’an. Wouldn’t it have made more sense for Chazal to make their point about not standing out with regard to Yaakov’s neighbors, the Cna’anim? There’s no reason to believe that Esav and Yishmael’s people were nearby.

What occurs to me is that there is a poignant prescience in Chazal’s comment. They may have sensed, or even foreseen, a distant but long-running future of Klal Yisrael, where so many of its members would be residing, as has been the case for many centuries, amid cultures associated with Esav and Yishmael.

© 2024 Rabbi Avi Shafran

It wasn’t very long ago that the idea of government funds helping parents who choose private religious schools for their children was anathema. That’s blessedly no longer the case. To read about what may lie on the horizon, please click here.

The nature of the “work” that Yosef came to Potifar’s house to do on the day when the Egyptian’s wife sought to entice him to sin with her (Beraishis 39:11) is famously the subject of a disagreement between Rav and Shmuel.

One opinion is that Yosef intended “to do his [household] duties”; and the other, “to do his needs,” i.e. to submit to the woman’s blandishments – an intention that was undermined only after an image of Yaakov appeared to Yosef, giving him the strength to resist (Sotah 36b). (That latter opinion, with its portrayal of Yosef as vacillating before finally resisting may be audibly symbolized by the shalsheles cantillation of the word vayima’en, “and he resisted.”)

Rav Simcha Bunim of Pshischa is quoted to have commented that the word “work” employed at the pivotal point in Yosef’s life – when he earned the appellation tzaddik, “righteous” – holds the message that each of us has a “work” to accomplish in his life, not just in a general sense but with regard to acting – or not acting – at a pivotal moment, when we are faced with a decision that will define us.

Yosef’s life-changing moment was when he was faced with an insistent Mrs. Potifar. Every person, the Pshischer suggested, will be faced with a pivotal moment, or moments, of his own, when his choice will make all the difference.

Which idea may lie behind Targum Onkelos’ translation of “his work.” He renders it in Aramaic as: “to audit his [Potifar’s] financial records.”

While that may simply be a presaging of the time-honored Jewish profession of accounting, the word Onkelos uses for “his financial records” is chushbenei. The word’s root is cheshbon, “accounting,” and it brings to mind its use in the phrase cheshbon hanefesh – an accounting of one’s “soul,” an examination of one’s standing in his spiritual life.

Each of us is charged with discerning moments in life, when the choice before us may be pivotal. Of course, we never know whether what we are facing is indeed such a moment. And so, we are wise to treat every decision we face as potentially momentous.

© 2024 Rabbi Avi Shafran

On a recent Friday night, the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) held its “30th anniversary gala” in Washington, DC. Too bad you probably missed it.

Something the celebrants didn’t know was that some bad news (at least for them) lay on the horizon. To read what it was, please click here.

Imagine finding yourself in a desolate place and spying a lone figure in the distance coming toward you. Your apprehension, even nervousness, would be understandable. But then, when he comes closer and you see that it’s a man with a long white beard, wearing a hat, kapoteh and tallis, you’d breathe a sigh of relief. Until he suddenly attacks you, gets you in a headlock and bends your arm painfully behind your back.

The angel that confronted Yaakov when our forefather re-crossed Nachal Yabok to retrieve some small items looked, according to one opinion, “like a talmid chacham” [Chullin 91a].

The most straightforward takeaway from that contention is that one cannot rely on the appearance of a person as being reflective of his essence. That’s an important lesson, as it happens, for all of us, and to be imparted to our young. Honoring someone who looks honorable is fine, but trusting him requires more than that.

But there’s a broader, historical message in that image of a faux talmid chacham too.

From the 19th century Wissenschaft des Judentums movement to the Reform and Conservative ones to the Jewish nationalism that sought to replace Torah with a Jewish state to “Open Orthodoxy,” there have been many efforts to distort the essence of Judaism – dedication to the Creator and His laws for us.

They have all sought to don conceptual garb proclaiming their “Jewish” bona fides. But they have all been revealed to be no less masqueraders than the sar of Esav wrapped in a tallis.

© 2024 Rabbi Avi Shafran