An article of mine about American society’s ambivalence regarding suicide appeared yesterday on Fox News – Opinion, and can be read here.

An article of mine about American society’s ambivalence regarding suicide appeared yesterday on Fox News – Opinion, and can be read here.

Across an ocean but hot on the heels of Congresswoman Ilhan Omar’s not-so-subtle invoking of the hoary stereotype of Jews’ wily wielding of wealth – “It’s all about the Benjamins,” she contended, referring to $100 bills and pro-Israel influence on Congress – comes an exhibit at London’s Jewish Museum titled “Jews, Money, Myth.”

It features, well, a wealth of anti-Semitic imagery, from an 1807 British board game called “Game of the Jew” to a money-dispensing figurine of an Orthodox Jew sold last year in Poland. Other awful offerings include the opening sentences from a Nazi-era children’s book. “Money is the god of the Jew,” the Teutonic tykes were tutored. “He commits the greatest crimes to earn money. He won’t rest until he can sit on a great sack of money.” And a helpful cartoon of that image ensures that the lesson was learned.

Greed, of course, is a pan-human phenomenon. But if any lives are lived in obsession over possessions and the means of acquiring them, it’s those of the typical westerner, craving cars, music, jewelry, clothing and high-tech toys. Most Orthodox Jews – who are those usually depicted in the ugly imagery – have always had more rarified priorities in life.

And yet it is the Jew who is accused of obsession with money. Jewish success born of business acumen and, more importantly, divine blessing has for centuries been twisted into the ugly trope that Jews are more prone to greed and malfeasance than other groups of humanity.

We aren’t, of course, but since when has anti-Semitism ever been linked to logic?

There’s an “on the other hand,” though, here. Because there is a kernel of truth to the charge that we believing Jews have a special relationship with money.

Rabi Elazar informs us (Chulin 91a) that Yaakov Avinu was dangerously “left alone” at Nachal Yabok because he crossed back over the river to retrieve some pachim ketanim, small jars. A lesson to us, the Tanna explains, that “the property of the righteous is dearer to them than their bodies.”

That comment is not meant to counsel miserliness; it conveys an important Jewish thought: Every penny has true worth, for it can be turned into something meaningful. We might think of someone who rinses out and re-uses foam cups as some sort of miser; and maybe he is. But the cups might also be his pachim ketanim, and he might also be a righteous man, reluctant to waste something usable. If he’s generous to the needy, we know which one he is.

And so, while stinginess is ugly, frugality is not. It is a meaningful Jewish trait.

Money’s worth is not only a function of what Rabi Elazar observes elsewhere, that “Each and every penny contributes to a large sum” (Bava Basra, 9b), but because there is inherent value in every thing. As Rabi Yitzchak reveals (ibid), “One who gives a penny to a poor person is blessed with six brachos.” Pretty good deal.

Money, moreover, offers us opportunities for honesty. A believing Jew carefully keeps an accounting of his assets and obligations – including his debts and charitable responsibilities.

And cash can yield great Kiddush Hashem as well.

My wife and I had the pleasure several weeks ago of spending a Shabbos in the lovely community of Scottsdale, Arizona, as guests of the local shul, Ahavas Torah, and its esteemed Rav, Rabbi Ariel Shoshan.

We stayed in the home of a Rebbi at the Torah Day School of Phoenix, Rabbi Noach Muroff, and his wife and family. Back in 2013, the Muroffs lived in Connecticut and Rabbi Muroff, an unassuming, modest person, found himself the subject of incredulous reports in international media. He had purchased a desk and discovered $98,000 that had fallen into the back of the piece of furniture. (During our stay, I wrote a Hamodia column on the desk!)

He decided to return the money to its owner, and a Gadol to whom he confided the story told him that it was an opportunity for a Kiddush Hashem that shouldn’t be squandered. And so a member of the media was apprised of the happening, and the rest was, as they say, history.

Many might have counseled the Muroffs to just keep the windfall. After all, they had bought the desk “as is.” But farther-seeing eyes counseled otherwise. And the world saw a true picture of how a Jewish-minded Jew looks at money, as a valuable means, not a meaningless end.

He may have forfeited a large sum, but, actually, he got a really great deal.

© 2019 Hamodia

When Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu got into a dustup with a television personality and a movie star, many of us felt reasonably secure assuming which side was likely more Jewishly authentic. And since the disagreement involved Israel’s relationship to the Jewish people, all the more so.

Sometimes, though, reasonable assumptions must give way to history and hashkafah.

The ruckus began with Mr. Netanyahu’s statement that Israel is “the national state, not of all its citizens, but only of the Jewish people.” That declaration – like the Knesset’s passage last year of a new Basic Law titled “Israel as the Nation State of the Jewish People” – was regarded by some as compromising Israel’s democratic spirit. And it drew fire not only from the political left and celebrities but even from people like Israeli President Reuven Rivlin.

In his dissent, Mr. Rivlin emphasized Israel’s “complete equality of rights for all its citizens,” and that “there are no first-class citizens, and there are no second-class voters… We are all represented at the Knesset.”

On one level, the argument is mere semantics. Mr. Netanyahu does not deny Arab Israelis’ right to vote or be represented in the Knesset. And Mr. Rivlin surely subscribes to Israel’s foundational self-definition as a “Jewish State.”

That self-description, of course, is no more a violation of democratic principles than Tunisia’s or Morocco’s self-definitions as Muslim states; or Argentina’s or Sweden’s or England’s as Christian ones.

But it’s election season in Israel, and it is to Mr. Netanyahu’s advantage to portray himself as an adversary of Arabs. His camp has popularized the phrase, “Either Bibi or Tibi” – a reference to Arab Knesset member Ahmed Tibi – even though the prime minister’s actual challenger is the Blue and White Party’s Benny Gantz. (I’m personally rooting, as are Israel’s religious parties, for Bibi, just describing a campaign reality.)

And yet, the “Jewish state” controversy touches on an important issue worth some renewed contemplation by Jews committed to mesorah.

Before the founding of Israel, there was opposition among Gedolei Yisrael to the idea of Zionism, the quest to establish a Jewish state. The reasons for the opposition were several and compelling; here is not the place to expound on them. After Churban Europa, though, the horrifically altered situation brought the Gedolim who guided Agudas Yisrael to adopt what might best be characterized as a non-Zionist stance.

With Israel’s declaration of independence in 1948, those Gedolim decided that the state should be appreciated for what it was but essentially regarded as a political state like any other, even if one founded by and for Jews. Rav Reuvain Grozovsky, zt”l, eloquently expressed the Agudah philosophy in his concise but persuasive kuntres Ba’ayos Haz’man.

Thus, followers of Agudas Yisrael voted, and vote, in Israeli elections, and the movement sponsored an official political party in Israel that, to this day, plays a role – often pivotal – in the formation of Israeli governments. The party, today part of Yahadus HaTorah, or United Torah Judaism, is largely focused on defending the religious status quo agreed to by Israel’s future leaders in 1947, and on advocacy on behalf of Israel’s religious Jewish community.

Eretz Yisrael, precisely as the phrase translates, is the land of the Jews – the territory promised by Hashem to Avraham Avinu and populated by his descendants in the time of Yehoshua. The connection of Klal Yisrael to Eretz Yisrael is undeniable, unmalleable and eternal.

But the modern state of Israel, at least to the followers of the Gedolim who have guided Agudas Yisrael, is a political state in an era of galus, not some semblance of Malchus Beis David.

A non-Zionist “Agudist” Jew can embrace a hawkish attitude toward Israel’s defense; fully recognize radical Arab groups’ threat to Israel; condemn the Palestinian Authority’s detestable incitement against Israel; have and express deep appreciation of Israeli soldiers; and support Israel morally, politically and financially. But, unlike his national-religious counterparts, he sees Israel as a largely praiseworthy country, a refuge and protector of Jews, but not as an inherently hallowed entity.

Proponents of both a religiously-motivated embrace of political Zionism and a mesorah-based worldview agree that Israel is a country for Jews in the Jewish homeland that maintains respect for aspects of Jewish tradition.

But it seems to me – and, as always in this space, I speak only for myself – that the mesorah-based outlook on Israel does not comport well with any message, however motivated and however subtle, to Israel’s Arab citizens that they are in any way lesser parts of the country’s body politic.

© 2019 Hamodia

Like most people, I have all sorts of complaints about the world. That is to say, about some of the people in it.

Like those who don’t know how to disagree agreeably, and consider every holder of a different opinion to be a mortal enemy.

And drivers who don’t bother to signal before turning or changing lanes. Likewise, those who don’t know how to properly double-park. (You have to leave a car’s width plus a half-inch for others to pass.)

And, of course, phone marketers, “survey” takers and politicians who interrupt the dinnertime calm with chain-call messages. Ditto for worthy causes that do the same, and somehow think that shouting in Yiddish will make the recipients more receptive to their cause.

I also have a bimah-ful of gripes revolving around shul.

Talking during davening is wrong. Not just disturbing to others and not just impolite. Wrong. Ditto for literally throwing tzedakah literature in front of people trying to daven. Double-ditto for those who don’t bother to turn off their phones before entering a mikdash me’at, treating it more like a shuk me’at.

The Sdei Chemed (Maareches Beis Haknesses, 21) cites the Magen Avraham and Chasam Sofer to the effect that any behavior considered disrespectful in a society’s non-Jewish houses of worship becomes, as a result, forbidden in Jewish shuls.

Maybe there are churches or mosques where congregants “warm up” for services by discussing business or sports or the stock market.Or who take the opportunity of a pause to schmooze or share jokes. But I wonder.

I have never had aspirations to being a shul Rav. My esteemed and much-missed father, a”h, was one, and watching him over the half-century of his exemplary service to his kehillah disabused me of any desire to undertake the myriad responsibilities that he shouldered so well. Even were I qualified for such a role, I don’t think I would be able to live up to his example.

And it’s probably a brachah for the world that I chose a different path, first, as a mechanech; then, as an organizational representative and writer. Because were I responsible for a shul, I would be a terror.

Not only would davening be stopped at the slightest hint of a conversation, but I would disallow chazzanus at the amud. Spirited, heartfelt singing would be fine, even invited. But “performances” would be canceled mid-concert. The tefillos, sir, just the tefillos.

If a cellphone rang – or beeped or pinged or chirped or played a merry tune – in shul, its owner would be presented with a pre-printed notice advising him that a first offense had been noted and that a second one would result in the gabbai’s confiscation of the offending device and its smashing with the special hammer kept under the bimah for that purpose.

Oh, yes, I would be a fearsome clergyman.

What is more, I would lock the doors once davening began.

Yes, lock them, so that no one could enter.

Some people approach tefillah as something they are supposed to do, which, of course, they are. But without much thought to concentrating on the meaning of what they are saying. There’s a reason for the expression “to daven uhp” something – i.e. to just read it quickly and perfunctorily.

Others are determined to maintain kavanah for every word of tefillah. They are usually the ones who are still davening Shemoneh Esrei when chazaras hashatz is almost completed.

Then there are the rest of us, who are still working on trying to keep our minds focused on what we are saying. Unlike the accomplished group, we are all too easily disturbed in our efforts by latecomers who open and close doors, and plod around noisily.

And so, the doors would be locked. And mispallelim would learn that arriving on time is important.

And, finally, to offend anyone I haven’t yet alienated, I would abolish all candymen. I might be persuaded to permit them to quietly place a (preferably low-sugar) treat in front of a child who’s davening nicely. But to just play Pied Piper, attracting a crowd of kids with a bag of tooth-rotting, empty calorie-laden goodies… not on my watch!

I realize that my dream of a shul is someone else’s nightmare, that the world is probably best off for the fact that I didn’t try to become a shul Rav.

Probably…

Yes, I know the causes of my gripes aren’t likely to disappear.

But could people at least start signaling before changing lanes?

A article of mine about Alexandria Ocasion-Cortez, distributed by the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, can be read here.

I suppose it’s not so strange that I put the two experiences together. They happened a mere day apart and both involved buses.

The first incident astounded me. As I stood in a line of people waiting to board an end-of-the-day bus at the Staten Island Ferry terminal, a young woman just walked up to the front of the line and, with nary a glance at anyone behind her, boarded the bus. Had she joined the back of the line as is normative, the seat she graced with her occupancy would have gone to someone else, perhaps one of the senior citizens who ended up standing during the ride.

The lady had no obvious physical impairment. She just seemed oblivious to the fact that other people occupy the universe, some even in her immediate vicinity.

I think I know what the line-cutter would have answered if asked how she would like it if someone stepped in a line in front of her. She would explain that, yes, she would have been angry, but that isn’t what happened; it was she who was entering the line out of turn, not someone else.

Empathy-impairment is an impressive thing.

We don’t start life off empathetic. Rav Yaakov Weinberg, zt”l, once mused aloud to me that there’s nothing more self-centered than a baby, and that’s probably why Hashem makes them so endearing; otherwise we might not properly care for the selfish little people.

But who can – emphasis on “can” – grow into empathic adults.

I remember how, as a little boy, I tested a magnifying glass I had received by focusing sunlight with it onto pieces of paper, charring them. And how I then – ugh – “graduated” to weaponizing my educational tool by using it to incinerate ants. Some experts claim that killing insects as a child presages the eventual emergence of a serial killer. So far, though, baruch Hashem, I haven’t much felt the urge to murder; when I have, have managed to overcome it.

In fact, today, when an insect finds its way into my home, I capture the invader and escort him or her safely to the great outdoors. (All right, not mosquitos; but they are aggressors.)

After all, how would I like it if someone chose to squash or flush me away?

Being concerned with the wellbeing of an insect is a low rung on the empathy ladder. The ultimate and most powerful concern for “the other” is for other people.

Which brings me to the second bus incident. The next morning, I boarded a mass transit vehicle that takes a rather convoluted route. It was the first time, apparently, that the driver had driven the route and before any passenger could stop him, he turned into a one-way street. A dead end.

It was a narrow street, and the “three-way turn” that the driver of a car might execute wasn’t an option. Backing up would be tricky.

I waited for the expected New York reaction, passengers’ grumbling and shouting of insults at the hapless driver. A pleasant surprise, though, awaited me. Not only didn’t my fellow travelers vent their collective spleen, many of them rushed to reassure the mortified man at the wheel not to feel badly. One man offered to stand behind the bus and direct its delicate backing out of the cul de sac, which was successful.

Everyone knew we would miss the ferry we had hoped to catch that morning. But everyone just cheered the driver, who was clearly happy with his lot – of passengers. Who, instead of being self-centered, demonstrated empathy.

People gauge gadlus ha’adam by many things. But the most essential marker of human growth may well be how far one has progressed from the selfishness that defines us at birth toward true empathy. The severely empathy-impaired, like the young woman on the bus line (and psychopaths), are essentially infants.

For members of Klal Yisrael, the import of empathy is evident in Rabi Akiva’s statement (quoted by Rashi) that the passuk “Love your fellow as yourself” (Vayikra, 19:18) is a “great principle of the Torah.” And in Hillel’s response to the man who insisted on learning the entire Torah on one foot: “What is hateful to you do not do to your fellow. That is the whole Torah; the rest is the explanation; go and study it” (Shabbos, 31a).

But dedication to an “other” is, in its most sublime form, expressed as selfless dedication to the Other. We are born selfish; and meant to strive toward concern for our fellows, but, ultimately, for the will of Hashem.

© 2019 Hamodia

To his great credit, President Trump didn’t allow the testimony of his former lawyer Michael Cohen before a Congressional committee to pressure him into making a deal at all costs with North Korea.

It would have been helpful to the president’s image to have upstaged the Cohen hearing last Wednesday with the signing of an agreement with North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un – a signing ceremony had in fact been scheduled – pushing Mr. Cohen’s allegations of the president’s ethical and moral turpitude to second place in the day’s news cycle.

But, despite the two days the American and North Korean leaders spent together in Hanoi at their second summit, there was no diplomatic triumph to announce, not even the usual joint statement expected after such talks.

Things apparently broke down when it became clear that the North Korean despot was unwilling to even disclose the number and locations of his country’s nuclear weapon sites until some economic sanctions against his country were lifted. And even then, reportedly, he was prepared to shut down only one of his reactors. Mr. Trump, laudably, would not agree to that, even if it meant that news organizations would be focused on Mr. Cohen’s harsh disparagement of his former boss.

Less laudably, the president responded to a question about the American Jewish college student Otto Warmbier, who was arrested in North Korea for allegedly stealing a propaganda sign and died six days after he was repatriated to the U.S. in a coma, by relating that Mr. Kim denied knowledge at the time of the student’s deterioration in a North Korean prison, “feels very badly” about it, and that he, Mr. Trump, takes the Korean leader “at his word.” (He later said that his words were “misinterpreted.”)

Mere hours later, true to form, Nikki Haley, Mr. Trump’s former ambassador to the United Nations, tweeted starkly that “Americans know the cruelty that was placed on Otto Warmbier by the North Korean regime.”

The president, of course, may have just been trying to be diplomatic, with the goal of achieving some future actual progress on North Korea’s nuclear disarmament, and may harbor very different feelings about his summit partner than he verbally expressed. If he does, he is justified.

Shortly before the summit, a collection of accounts from North Korean defectors and North Korean officials in China was released, under the title “Executions and Purges of North Korean Elites: An Investigation into Genocide Based on High-Ranking Officials’ Testimonies,” by the Seoul-based North Korean Strategy Centre (NKSC).

It offered chilling accounts of utter contempt for human rights and numerous murders, claiming that Mr. Kim has had 421 officials executed and exiled since seizing power in 2011. Some victims, it reported, had been thrown unclothed to vicious hunting dogs; others were killed with shells; others still, burned alive with flamethrowers.

In some cases, the report asserted, entire families of officials have been executed or were imprisoned in concentration camps and “erased from society.” Officials faced death or imprisonment, the report alleges, for minor infractions like improper posture at an event attended by “supreme leader” Kim.

Mr. Kim is also said to have ordered the execution of his own family members, including his uncle Jang Song Thaek, who was killed along with his associates in 2013 (for having “sold the country’s resources to foreign countries at a low price”), and his half-brother Jong-nam, who was assassinated at a Malaysian airport in 2017.

A former student at Pyongyang Commercial College, identified only as “Moon,” is quoted in the report as claiming to have witnessed a 12-man public execution by soldiers using anti-aircraft guns. Armored vehicles then reportedly crushed their remains.

Evil tends to dovetail with Jew-hatred, of course. And that may be why North Korea sent pilots to Egypt during the Yom Kippur War, more recently helped Syria construct a nuclear reactor and recognizes the sovereignty of the non-existent “State of Palestine” over all of Israel, except for the Golan Heights (which it considers as part of Syria).

There are, of course, despots at the helm of other countries with which the U.S. has made strategic alliances over the years. And such associations, disturbing as they are, are not always the worst of the available options.

But it is hard to find a parallel, outside the example of Nazi Germany, to the sort of flagrant monstrousness that credible witnesses have described as an essential characteristic of the Korean peninsula’s hermit kingdom.

Iran, still abiding by the 2015 multi-nation deal, isn’t currently an immediate nuclear threat to others.

North Korea, though, is. And President Trump should not rest until it, too, is constrained.

© 2019 Hamodia

There’s no point in further delaying the news. I will soon be officially announcing my candidacy for the presidency of the United States. Most everyone else has done so and I don’t want to be left out.

The official throwing of my hat (my weekday one, as it needs replacing anyway) into the presidential ring will take place at Hamodia’s sprawling Borough Park offices at a date and time to be announced.

I will be running on the Purim Party ticket, and am currently accepting applications for the position of running mate. My life mate, unfortunately, does not qualify, as she was not born in the U.S.; in fact, she obstinately remains a Canadian citizen, an alien (in more ways, perhaps, than one, since, as numerous immigration officials at Newark airport can attest, she lacks detectable fingerprints).

My personal qualifications are well-known. I was a candle in my kindergarten Chanukah production, and graduated both elementary and high school. And I have no felony convictions.

I have never knowingly employed undocumented domestic help, and have never worn blackface. There was that do-rag a few Purims back, yes, but there are no photos that I know of. (Should you have any, please be in touch with my fixer, the aforementioned Mrs. Shafran.)

My closet, although it’s cluttered, holds no skeletons, only an assortment of old ties biding their time until they are once again of fashionable width.

And so, I feel that I am eminently qualified to occupy the seat once occupied by the venerable likes of Millard Fillmore and Warren Harding.

My platform? Thank you for asking. I support universal health care, universal child care and universal common sense training, something I’ve long felt has been sorely lacking in American society.

I have no position on minimum wage, but support a maximum one.

The Middle East will be one of my top priorities, of course. I have a secret peace plan. No, of course I can’t offer it; if I did, it wouldn’t be secret, would it? (Common sense training would have made that explanation unnecessary.)

I also look forward during my tenure, to appointing Supreme Court justices who are practicing Orthodox Jews, ideally kollel-leit and BJJ graduates.

But my campaign mantra, with which I expect my supporters to drown me out at rallies when I start rambling incoherently, will be “Build the Wall!” No, it has not been copyrighted (I checked), and, in any event, it’s not a southern border wall I will be urging, but a northern one.

Yes, as you know, there is an urgent need for a 3000-mile-long impenetrable barrier between our mainland and Canada, to protect our beloved country from the dire threat poised to invade from the north – the forces of civility and polite discourse.

Now, Canadians are welcome to embrace such un-American practices in their own country if that’s really what they want. Hockey pucks to the head and beer overconsumption take a toll on a society. But the peril posed by an import of politeness to our own political sphere is frightening.

Name-calling and personal insults, after all, are part of the republic’s DNA. We must never forget our twin guiding principles, e pluribus unum and argumentum ad hominem.

When Thomas Jefferson called John Adams a “repulsive pedant” and a “hideous… character,” the gauntlet was thrown, and it was picked up by Mr. Adams, who labeled Mr. Jefferson a “G-dless atheist” and cast crude aspersions on his parentage.

Adams’ son John Quincy played the genealogy card himself, against Andrew Jackson, disparaging the latter’s mother; and Mr. Jackson made sure that the media, which wasn’t yet fake, called JQA’s moral behavior into question.

Memorably, Stephen Douglas’ supporters called Abraham Lincoln a “horrid-looking wretch” who was “sooty and scoundrelly in aspect, a cross between the nutmeg dealer, the horse-swapper, and the nightman.” (“Nutmeg dealer”? I have no idea.) For his part, Honest Abe compared Mr. Douglas to an “obstinate animal.”

Teddy Roosevelt famously referred to William Howard Taft as “a rat in a corner.”

More recent examples of the glorious rudeness that imbues the American political realm from all its corners are readily available from news organizations, Twitter and local bars.

And, so, it is clear that we must do all we can to avoid a slippery slide into civility. Invaders from the north may only be targeting mudslinging today, but tomorrow it will be baseball, and before we know it, they’ll be coming for our guns.

So, if you care about the U.S.A., you know your choice!

© 2019 Hamodia

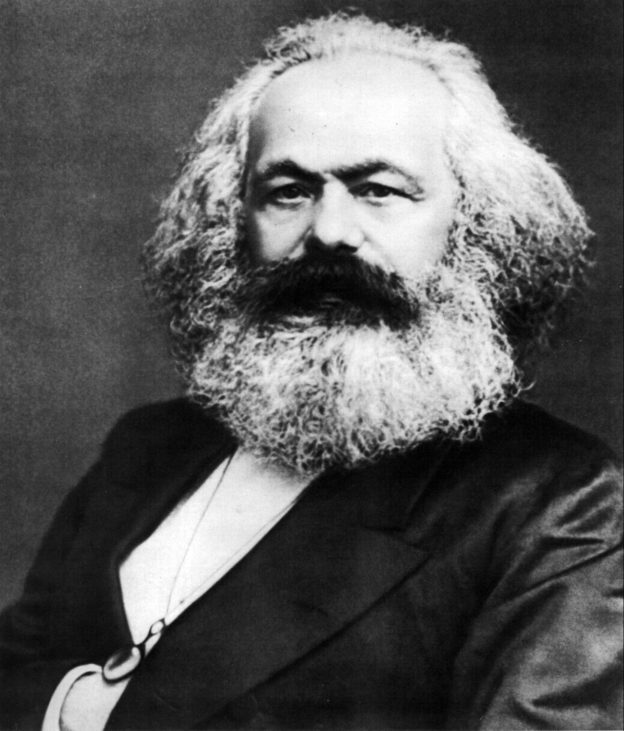

Back in 1947, a public relations firm called Whitaker and Baxter, hired by the American Medical Association, created a term to disparage President Harry Truman’s proposal for a national health-care system.

It was a stroke of PR genius, at the dawn of the cold war between the U.S. and the communist Soviet Union, when many Americans feared communist infiltration of the republic, to label Truman’s plan for universal health care “socialized medicine.” Nearly thirty years after the fall of the Soviet Union, the phrase endures, along with at least some of the accompanying disdain it was designed to evoke.

The A.M.A. ran with the medicine ball and distributed posters to doctors with slogans like “Socialized medicine … will undermine the democratic form of government.”

Fast-forward seven decades. Universal health care is shaping up to be one of, if not the, defining issues of the 2020 presidential campaign, and in some circles is being labeled “socialist.” And indeed it is, at least in the word’s more benign definition.

Some words or phrases, of course, don’t always mean what they might seem to on the surface. Like “Important!” in the subject box of an e-mail, which almost always means the opposite. Or “a service representative will be with you shortly” on a phone call, which usually turns out to be a bald lie. “Socialist,” too, doesn’t necessarily mean what it once did.

Back in the day, a socialist was a close ideological cousin of a communist. Socialism as a governmental system may have lacked the communist element of totalitarianism and total control of people’s lives; but it still placed ownership of all means of production in the hands of the populace, with members of society receiving what they need but having no incentive to work hard to achieve anything more.

But socialism as an all-encompassing, coercive system of government is something distinct from governmental programs aimed at providing safety nets to citizens. Like Social Security, for example, or Medicare or, for that matter, the public school system. All are “socialist” creatures, at least in the sense that they are government-run and aimed at ensuring certain benefits for the entire citizenry.

Universal health care, which has been endorsed as a desideratum by a number of Democratic candidates for the nation’s highest office, is “socialist” too, for sharing the same aim – here, to ensure that all Americans have access to doctors, hospitals and medications.

As it happens, though, even “universal health care” – reflected in the increasingly popular mantra “Medicare for all,” which is becoming the Democratic counterpart to Republicans’ “Build the wall!” – has different meanings. Or, at least, there are very different vehicles for achieving that goal.

The idea of providing health care to all Americans is simple enough. But there is a den of devils in the details.

For some, like Senators Bernie Sanders, Kamala Harris and Elizabeth Warren, the way to go is a national, “single-payer” health system, in which private insurance is abolished. (As you might imagine, insurance companies are not fans of such a plan.) All sorts of costs born of the way insurance interests operate would presumably be eliminated, and medical care streamlined.

That’s the upside. The downside is that the insurance companies’ replacement would be the federal government. Frightening as that may be to some, and imperfect as such systems are in places like Great Britain and Canada, most Americans feel that the feds have done a decent job running Medicare. Back on the other hand, though, a “single payer” approach would likely mean higher taxes.

Other plans are mixtures of government and private insurers. In Switzerland, for instance, citizens buy insurance for themselves and pay deductibles, but the government subsidizes health care on an income-based graduated basis,

Then there is the approach of offering citizens discounts on government-sponsored health insurance plans, and expanding the Medicaid assistance program to include more people who can’t afford health care. That is the essential feature of something called Obamacare, the current system in place.

As in all large governmental efforts, achieving universal health care in the U.S. is a stupendously complex undertaking. But six out of ten Americans say it is the federal government’s responsibility to make it happen. The U.S., in fact, is the only wealthy industrial country in the world lacking such a system.

I’m not sufficiently proficient in assessing the necessary calculi to offer any opinion about which health-care path is the best way forward. What I do know, though, is that whatever approach ends up being chosen by the electorate, it won’t be the sort of socialism Americans once feared was lurking under the bed.

© 2019 Hamodia

Many of us pale-skinned Americans are puzzled by our darker-skinned fellow citizens’ strong negative reaction to the practice of “blackface” – Caucasians putting on black makeup to portray African-Americans.

The issue burst into the news cycle with the admission of Virginia Governor Ralph Northam that he had once applied such coloration in a contest where he was imitating a black entertainer. Mr. Northam’s 1984 Eastern Virginia Medical School yearbook page also featured a photo, among several anodyne ones, of a blackfaced person standing next to someone wearing a makeshift costume meant to evoke a Ku Klux Klan robe. Although the governor initially apologized for that image, he later denied that either man was him.

Calls for Governor Northam’s’s resignation came fast, furious and loud, and from multiple directions, including from Mr. Northam’s fellow Democratic elected officials. Improbably, the second in line to succeed the governor should he step down (the first in line, the lieutenant governor, stands accused of assault), the state attorney general, also confessed to wearing blackface in the 1980s.

The vehemence of the reaction to the governor’s admission was striking. The yearbook photo seemed to be from a costume party and, while in bad taste, didn’t seem to be overtly racist or threatening; and he insists he is not even in it. As to the contest imitation admission, well, he was imitating a black performer. Was the smear of makeup really so terrible?

For those of us who don’t carry the weight of America’s racialist history and the undeniable challenges, and dangers, of black life today, there’s much to unpack here.

And Chazal provide instructions for the unpacking, in Avos (2:4), directing us to “not judge another until you have come to his place.” Whether or not that directive applies universally, it is a logically compelling admonition in any context, and no one who hasn’t experienced what blacks do daily can claim to fully understand their feelings.

As to blackface, while it has been used innocently in productions over many years – as recently as 2015, a white singer for the Metropolitan Opera used it to portray a Shakespearian character – it also has a sordid history of being used to demean and mock black people. Minstrel shows, where white performers wore blackface to depict African-Americans disparagingly, were once immensely popular, particularly in the south.

An imperfect comparison might be how we Jews might feel about an even innocuous use of a swastika at a party or contest. Swastikas, too, can be used innocently, and a Thai entertainer recently sported one, knowing it only as an ancient Asian symbol of good luck.

But even those of us who would not recoil at the casual use of that horrific symbol and regard blackface as similarly unobjectionable would do well to consider another statement of Chazal, in Chagigah 5a, where Rav and Shmuel both consider it a sin to do even something that is inoffensive to many people – like squashing a bug or spitting on the ground – in front of someone who finds the act repulsive. It makes no difference, in other words, that the doer considers an action unobjectionable; if others who witness it will be offended, that’s reason enough to not act.

Mr. Northam isn’t likely familiar with Chazal. Perhaps he should have, on his own, recognized that blackface, even in a lighthearted singing contest, causes many blacks to feel pained and insulted. But that fact wasn’t as widely recognized decades ago as it is today.

People who attended medical school with Mr. Northam have asserted that he was not a prejudiced person. One of them, Dr. Giac Chan Nguyen-Tan, said that his former fellow student was “the furthest thing… from someone who is a racist or bigot.” Moreover, the governor’s record as an elected official on civil rights issues has been spotless.

Which has led a few commentators to take issue with all those calling for the Virginia governor’s resignation.

Former Senator Joe Lieberman, for example, suggested that, despite Mr. Northam’s blackface admission, “really, he ought to be judged in the context of his whole life” and not “rush[ed]… out of office…”

That strikes me as a most reasonable stance. Whether Mr. Lieberman’s approach, though, or that of those calling for Mr. Northam’s political head will ultimately prevail isn’t known at the time of this writing.

But regardless of whether Mr. Northam continues as Virginia’s governor, his travails have brought some healthful attention to the broader truth that people have sensitivities that others may not always be able to relate to personally. And the fact that we need to take care in our interactions, with fellow citizens, and with friends and family members, to accommodate them as best we can.

© 2019 Hamodia