Indiana Republican Congressman Todd Rokita is calling on the House of Representatives to condemn “Nation of Islam” leader Louis Farrakhan.

Most of us are familiar with the racist demagogue Mr. Farrakhan’s more memorable rantings, like “The white man is a devil by nature”; “Hitler was a very great man”; “We know that Jews are … plotting against us as we speak.” The calypso singer-turned-“reverend” has denied the Holocaust, blamed Jews for the 9/11 attacks, and said that white people “deserve to die.”

And just to make sure no one thinks he may have gone soft (or sane) in his dotage, just last month he railed that “powerful Jews are my enemy… responsible for… filth and degenerate behavior.”

As it happens, a resolution similar to the one Mr. Rokita proposed was passed overwhelmingly back in 1994 by a Democrat-controlled House. What motivated Mr. Rokita now was the fact that several current House Democrats – including Democratic National Committee Deputy Chair Keith Ellison, Danny Davis and Gregory Meeks – attended a dinner where Farrakhan was present or expressed respect in the past for the hatemonger.

Politics, though, is an unpleasant business, and associations of a sort with abhorrent people who have sizable followings is more common than the more innocent among us may realize. A photo of then-Senator Barack Obama posing for a “grip-and-grin” with Farrakhan in 2005 recently came to light. It took a while for presidential candidate Donald Trump to finally disavow the support of David Duke.

What’s more, part of the American black community looks at Farrakhan and sees only a preacher of self-reliance and black pride. The man’s ugly hatred of others is, to them, just static. No, that should not be, but “should not” doesn’t change an “is.” That segment of the populace, moreover, bristles at being chastised for embracing whom they do, even when the embraced is morally decrepit.

As long-time Representative Charlie Rangel, a friend of the Jewish community – he flew to Israel when he was 85 for Shimon Peres’ funeral and headlined a 60th anniversary bash for Israel at Harlem’s Apollo Theater – put it in 1985, Farrakhan’s anti-Semitism is “garbage,” but “there is a lot of concern among a lot of blacks that they don’t want to be told what to do.”

The aforementioned Mr. Obama for years attended the church of a Farrakhan-like character, the infamous preacher Jeremiah Wright. When some of the latter’s more offensive oratory came to light in 2008, the then-presidential candidate disavowed his relationship with the preacher, left the church and called Wright’s comments “ reprehensible,” saying they provided “comfort to those who prey on hate.”

Messrs. Ellison, Davis and Meeks likewise all eventually condemned Farrakhan’s hateful rhetoric.

Mr. Ellison, who defended Farrakhan back in the 1980s and 1990s, has long expressed regret for doing so, calling it, as he titled a 2016 op-ed, “The Mistake in My Past.”

“These men organize,” he wrote of Farrakhan’s group, “by sowing hatred and division, including anti-Semitism…”

“They were and are anti-Semitic,” he once stated, “and I should have come to that conclusion earlier than I did. I regret that I didn’t.”

And Mr. Ellison has in fact enjoyed good relationships with his Jewish constituents and with Jewish members of Congress.

For his part, Mr. Davis said “Let me be clear: I reject, condemn and oppose Minister Farrakhan’s views and remarks regarding the Jewish people and the Jewish religion.”

The touchiness that Mr. Rangel referenced, though, was evident in Mr. Meeks’ comments. While he called Farrakhan’s anti-Semitic messages “upsetting and unacceptable,” he added that he is “still waiting for [right-wing blogs] to condemn [President] Trump’s racist remarks.”

Whatever one may think of the current occupant of the White House or his policies, though, he has never called any faith a “gutter religion,” praised a genocidal mass murderer or referred to any ethnicity as “bloodsuckers.” Mr. Meeks is free to criticize Mr. Trump all he wants. But placing him in the same universe as Farrakhan is madness.

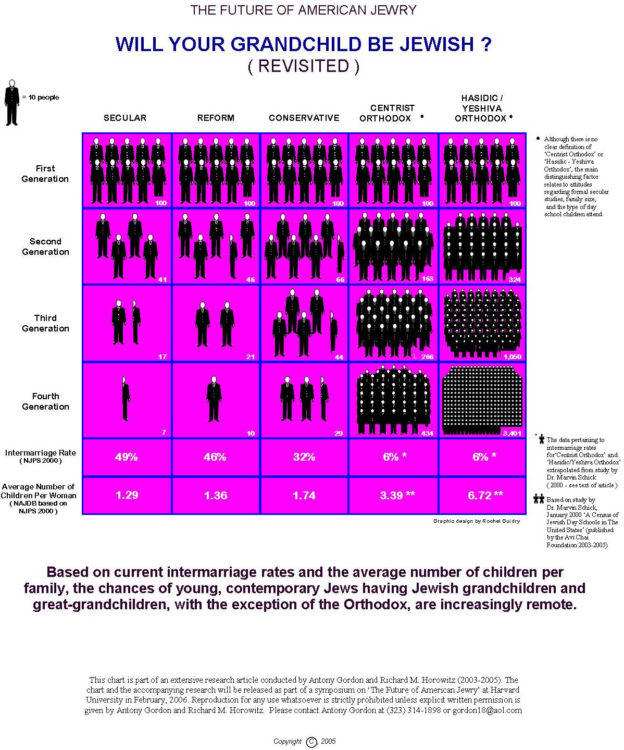

Jewish-black relations have generally improved over the years. And on many domestic issues, the two populations are natural allies. Growing any relationship, though, requires a determined, honest effort to see through the eyes of the other. We Jews need to try better to understand why some in the African-American community could be temporarily oblivious to an ugly radical’s hatreds; and to raise our children to see people, not melanin.

And the black community needs to recognize and openly espouse, as the former president and the current House members have done, the grave injury done – not just to Jews but to humanity – by the presence of demagogues in its midst.

© 2018 Hamodia