When we read the account of Yosef’s unfair imprisonment – and his eventual release after the Egyptian ruler is informed by the sar hamashkim, the butler, of Yosef’s G-d-given ability to interpret dreams – there’s something that’s easily overlooked: the particular action that set Yosef’s liberation into motion.

Rav Yaakov Kaminetsky, zt”l, points out that the genesis of Yosef’s release from prison and ascension to the position of viceroy in Mitzrayim lies in his having noticed that his fellow prisoners, the king’s baker and butler, were crestfallen one morning.

He didn’t ignore that fact. “Why do you appear downcast today?” he asked them (Beraishis 40:7). And they proceeded to tell him of their dreams, which he then interpreted.

“Come and see,” Rav Kaminetsky advises, “the greatness of Yosef,” who, after being wrongly imprisoned by other Egyptian officials, nevertheless, when he saw these officials in a state of depression or angst, was so concerned that he immediately asked them what was wrong.

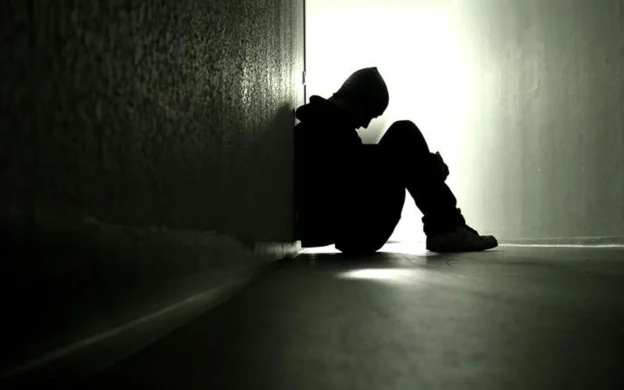

That’s a lesson for life. When we see someone out of sorts, we are often inclined to ignore the person or even steer ourselves in another direction. But it is that inclination to avoid the sad person that should be ignored. We may not have the solution to the depressed person’s problem like Yosef had for his fellow inmates’ dilemma. But asking “What’s wrong?” or “Can I help?” are the proper responses. If only because they are expressions of concern.

Which may help lift the spirits of the inquiree.

And even, perhaps, benefit the inquirer.

© 2023 Rabbi Avi Shafran