True or False?

- The U.S. abstention to the recent U.N. resolution was the first time an American administration declined to veto a Security Council resolution critical of Israel and opposed by her.

- The resolution is groundbreaking, and pledges the territory captured by Israel in 1967 to a Palestinian state.

- It would remove Yerushalayim and the Kosel Maaravi from Israeli sovereignty.

- It is one-sided, placing the blame for the stagnated peace process squarely on Israel.

- President Obama and Secretary of State Kerry have sold Israel out.

The first four are demonstrably false. The fifth, too.

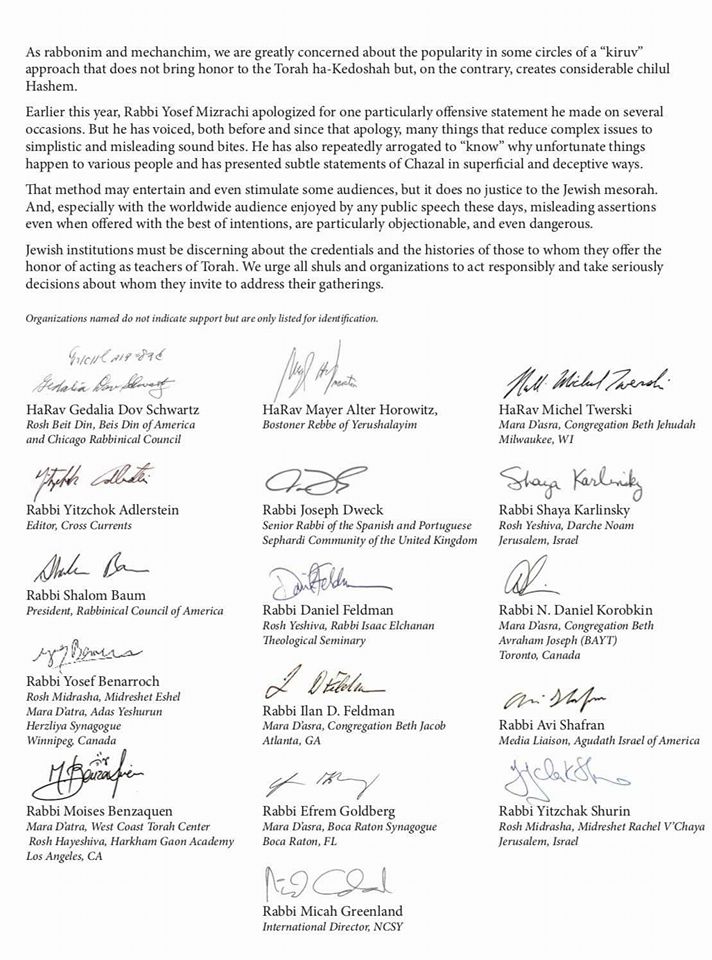

Please don’t read further if you are not willing to consider a perspective different from the one you expect from this rightly respected newspaper and other “pro-Israel” news sources and organizations, including the wonderful one that employs me, Agudath Israel of America, which, like many other Jewish groups, condemned the U.S. abstention. I am resolutely pro-Israel but not necessarily in agreement with every Israeli administration’s positions. And, as I have pointed out on several occasions, while I proudly represent Agudath Israel, and convey its stances to the public and media, I exist as an individual too, and I write in these pages and in others from my own personal perspective.

Still here? Good.

Since the Six-Day War in 1967, there have been 42 U.S. vetoes of Israel-critical resolutions – but, over the course of eight U.S. administrations, including the Reagan and George W. Bush years, more than 70 “yes” votes or abstentions. The recent Security Council abstention was noteworthy, though: it was the Obama administration’s first non-veto of a critical-of-Israel resolution in its eight years, the lowest count of any president since 1967.

The recent resolution has no practical effect and takes no position that has not already been taken by the Security Council (and most of the world’s governments). It does not determine borders; it only reiterates the tired truism that Yehudah and Shomron are “occupied” territory. Technically, that is not entirely accurate, since the land was not under any state’s legitimate sovereignty before its capture, but it is true that, of all the captured territory, only Yerushalayim was annexed by Israel.

And Yerushalayim’s status, although not recognized at present by the U.N., will not change in negotiations, should the peace process ever resume. As Secretary of State Kerry said in his detailed post-vote speech, there must be “freedom of access to the holy sites consistent with the established status quo.” He reiterated that point, too, a moment later, declaring that “the established status quo” at religious sites must be “maintained.”

U.N. resolutions concerning Israel have long been consistently, notoriously and laughably one-sided. This one, though, as it happens, while calling on Israel to stop building in settlements, calls too on Palestinians to take “immediate steps to prevent all acts of violence against civilians, including acts of terror” and to “to clearly condemn all acts of terrorism.” That, at least for the U.N., is in fact groundbreaking.

As to Messrs. Obama and Kerry, consider a thought experiment. Imagine – just as a theoretical possibility – that they both actually care deeply about Israel. In fact, over his nearly 30 years in the U.S. Senate, Mr. Kerry was a reliable, stalwart and unapologetic defender of Israel. Pretend that Mr. Obama is of similar mindset. (Which he is, but if you’re convinced otherwise, just pretend.) And that they both believe, honestly and deeply, that (whatever you or I may hold to be true) only a two-state solution can ensure Israel’s security and integrity, and that continued settlement-building gives the Palestinians an excuse (unjustified, but still) to not engage in peace negotiations.

What would the two men then rightly do, with only days left for their administration, if a resolution reiterating the world’s objection to that building activity and calling for negotiations were put on the Security Council table? Veto it, against their convictions about Israel’s wellbeing? Or try to send a message, as they prepare to leave the world stage, about what they feel is best for Israel?

They might be entirely wrong about that (although they might be right). And, yes, the overwhelming blame for the lack of peace is unarguably on the Palestinian leadership and populace. And yes, all of Eretz Yisrael is bequeathed to the Jewish People.

Still and all, the American leaders’ determination to issue a final, passive call for what they believe is in Israel’s best interest does not bespeak disdain for Israel, but precisely the opposite.

Which is why all the shouts of “betrayal!” and “traitors!” and “complicit!” are so very wrong and so very sad. This is an administration that has stood by Israel time and time again for eight years, and that mere months ago forged a 10-year, $38 billion military aid package for Israel, the largest for any U.S. ally ever.

One can consider Mr. Obama and Mr. Kerry (and most Israelis, as it happens, because a clear majority are in favor of a negotiated two-state resolution) misguided, if one must. But one cannot slander them as Israel-betrayers. Must everyone be either “with us” or “against us,” “friend” or “enemy”? Can no one be with us and a friend but with a different perspective than our own?

What the outgoing U.S. administration wants from Israel isn’t capitulation to her enemies. What it has always sought is a sign of willingness on the current Israeli government’s part to simply act decisively on its declared commitment to a peace process aimed at a two-state solution. To be sure, even a restarted peace process is far from assured of success; there are many issues that could prove intractable. And yes, there have been moratoriums on “disputed territories” building in the past, to no avail. But an acceptance of yet another one, instead of a continuation of the recently accelerated pace of building, will put the ball again in the Palestinian court, and offer something to an angry world.

Yes, that world is unreasonable, obnoxious and ugly. Not to mention ridiculously hyper-focused on Israel, when so many truly unspeakable true human tragedies exist elsewhere, ignored.

So why, so many ask, should its opinion matter to us? That sentiment is what Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu expressed when he said, in the wake of the Security Council vote, that “Israelis do not need to be lectured of the importance of peace by foreign leaders” and that “Israel is a country with national pride, and we don’t turn the other cheek” and that he has had “enough of this exile mentality.”

And it is what he expressed, too, by summoning ambassadors of countries who voted for the resolution, and the American ambassador as well, to reprimand them, on the day that Christians consider the holiest on their calendar. “What would they have said in Jerusalem,” an unnamed Western diplomat later fumed, “if we summoned the Israeli ambassador on Yom Kippur?” Think hard about that.

It may feel gratifying to snub one’s nose at real or perceived enemies. Personally, though, I am a talmid, so to speak, of Rav Elchonon Wasserman and Rav Reuvein Grozovsky, zecher tzaddikim liv’racha, not of Reb Bibi Netanyahu. I believe that we are indeed in exile, in galus; that “secular Jewish nationalism” is wrong and dangerous; and that a modicum of modesty is demanded of all Jews, especially those who claim to represent other Jews. I believe that humility, not arrogance (and certainly not “kochi v’otzem yadi”) should be the operative principle of Klal Yisrael, and of anyone who deigns to lead a “Jewish state.”

Maybe, with the help of the Trump administration, Israel will be able to cow the 2.8 million Palestinians in “the territories” into submission. And maybe Hamas will not be able to seize whatever peace-seeking Palestinian hearts and minds are left. Maybe all will be well, Israelis will sleep safely and the fears of the Obama administration will prove to have been without warrant.

Maybe.

But whatever may happen in the future, what the present requires of us, al pi mesoraseinu, I believe, is hatznea leches and hakaras hatov, not snubbing, sneering or insults.

© Hamodia 2017