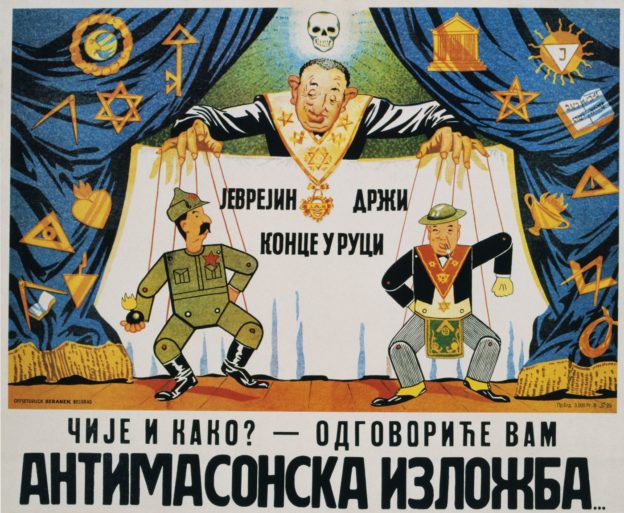

Like many identifiably Jewish Jews, I’ve caught my share of catcalls, Nazi salutes and threats. And read the rantings of people like Louis Farrakhan, David Duke and Richard Spencer. I can’t say I’m nonchalant about such idiocies, but a certain jadedness, for better or worse, eventually kicks in.

There are times, though, when even I am astonished by a particularly outrageous demonstration of mindless Jew-animus. Like Jersey City school board member Joan Terrell-Paige’s now-deleted Facebook comment, posted mere days after the murderous December 10 attack on the kosher market in her locale by two terrorists, one of whom had shown interest in a Jew-disparaging black sect. (One of the murderer’s favorite videos shows a Black Hebrew Israelite preacher telling a Jewish man, “The messiah, who is a black man, is going to kill you.”)

Ms. Terrell-Paige implied that, in effect, the killings had been brought about by “brutes in the Jewish community” themselves.

She charged that Chassidic newcomers to Jersey City had “waved bags of money” before black residents in order to buy their homes.

Leave aside that the Chassidim who have relocated from Brooklyn to Jersey City are decidedly not well-to-do; and leave aside, too, that asking a homeowner if he’s interested in selling a house isn’t illegal or oppressive. Leave aside as well the fact that the city enacted, with the support of its Chassidic residents, a prohibition of door-to-door solicitation.

Consider only the utter asininity of blaming innocent victims for the hate-driven actions of the racists who murdered them.

As if the arson of her words wasn’t sufficiently destructive, Ms. Terrell-Paige added fuel to her fire, too. “What is the message they were sending?” she asked, referring to the murderers. “Are we brave enough to explore the answer to their message? Are we brave enough to stop the assault on the Black communities of America?”

One wonders how the valiant lady would have reacted had someone asked her, in the wake of the violence perpetrated by white supremacists in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017, to be “brave enough” to consider what message those haters were sending by punching and kicking peaceful protesters (and injuring several and killing one with a car). If someone had suggested that she be “brave enough to stop the assault on White communities of America?”

Nearly as tone-deaf as the school board member’s post was the reaction to her mindlessness by a group that includes local and state legislators and calls itself the Hudson County Democratic Black Caucus.

“While we do not agree with the delivery of the statement made by Ms. Terrell-Paige,” the group announced judiciously, “we believe that her statement has heightened awareness around issues that must be addressed.”

No, dear Caucus, the only issue that must be addressed is black anti-Semitism.

That phrase, of course, isn’t intended to implicate the larger African-American community, any more than the phrase “white anti-Semitism” implicates all Caucasians.

It simply acknowledges the sad reality that Jew-hatred exists not only in the fever dreams of racists who hate blacks but also in the delusions of some of those they hate.

The group of legislators and community leaders of color did pay proper homage to the need to maintain good relations between “two communities that have already and must always continue to coexist harmoniously.” But that sentiment is belied by the rest of its statement’s cluelessness.

What the group needed to do after reading Ms. Terrell-Paige’s obnoxious words was not to speak of “issues” to be addressed but rather join Jersey City Mayor Steven Fulop, New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy, Jersey City Education Association President Ron Greco, Ward E Councilman James Solomon, New Jersey State Democratic Committee Chair John Currie, Board of Education Trustee Mussab Ali, and Assemblymen Nick Chiaravalloti, Raj Mukherji and Gary Schaer in their call for Ms. Terrell-Paige’s resignation.

As to the “issues” that the Hudson County Democratic Black Caucus says “must be addressed” – presumably those posed by the influx of Chassidim into Jersey City – let’s indeed address them.

Among the freedoms Americans are afforded is the right to live where they wish. The arrival of Jewish residents to a depressed neighborhood, moreover, is likely to contribute to the good of longer-term residents. There will be healthful food available (like some of that sold in the grocery that was turned into a scene of carnage), crime will likely decrease and property values rise.

Back in 2017, the New York Times featured an article about demographic changes, including those in Jersey City. It quoted a Jewish woman, identified only as Gitti, who expressed appreciation for her non-Jewish neighbors.

“They told us when we have to put out our garbage, and they introduced us to their pets so we shouldn’t be afraid of them,” she said. “They’re nice people.”

Eddie Sumpter, a black neighbor around the corner from Gitti’s home, who was able to buy a bigger house by selling his previous home to a Chassidic family, said he welcomed the newcomers.

“We live among Chinese. We live among Spanish,’’ said Mr. Sumpter, who works as a cook. “It don’t matter. People is people. If you’re good people, you’re good people.”

Unfortunately, it’s pretty clear, not everyone is.

© 2020 Hamodia