Your Uber driver might be pleasant to you because he values another human being, but his desire for a four-star rating likely plays a larger role in his affability.

A sure way to anger an atheist is to challenge him to explain why anyone should be pleasant, or ethical or moral – beyond the mere utilitarian gain of a social contract. He will jump up and down and insist that goodness and badness exist. But, in the end, without a Higher Power’s guidance, those words are utterly fungible. Good and bad behavior, sans a Divine Guide, carry no more ultimate meaning than good or bad weather. And flowers appreciate thunderstorms.

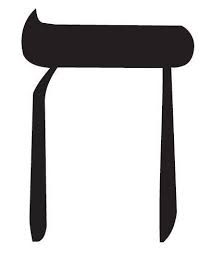

Parshas Mishpatim begins with the connection-letter vav, indicating that the laws that follow, many of them dealing with financial dealings, torts and other interpersonal matters, were, no less than the “Ten Commandments” and mizbei’ach laws of the previous parshah, “from Sinai,” as Rashi, quoting Midrash Tanchuma, notes.

Inherent in that vav-connector, says Rabbi Shlomo Yosef Zevin, is the fact that, for Jews, seemingly mundane business and interpersonal dealings are to be conducted ethically not as mere parts of a social contract but rather as the fulfilment of Divine command.

And, he continues, it is a distinction with a momentous difference. “Rivers of blood” have been spilled, he points out as an example, “up to and including the present,” as a result of human reinterpretation of “Thou shall not murder.”

When killing, or stealing, or harming others are only man-made social constructs, ways will be found to sidestep them or “clarify” their application when deemed necessary. By contrast, one who accepts the Torah’s ethical laws as a divine charge will perforce treat them as truly binding and absolute, no matter what.

Those with the custom of saying a “lishem yichud” declaration of holy intent before putting on tefillin or taking an esrog and lulav in hand generally don’t do so before signing a contract or treating another person pleasantly.

But there’s really no reason not to.

© 2026 Rabbi Avi Shafran