Senator Orrin G. Hatch’s announcement of his retirement at the end of the year brought me back to the summer of 1995. That’s when I returned to my family’s former home of Providence, Rhode Island to visit, for the last time, the Utah senator’s former speechwriter, one of the most fascinating people I have had the fortune of knowing.

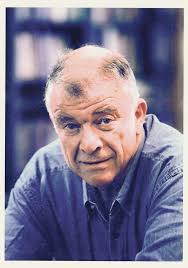

A scion of the Zhviller Chassidic dynasty, Rabbi Baruch Korff lay on his deathbed.

It was back in the 1970s that the erudite, eloquent Rabbi Korff worked without fanfare for Senator Hatch. To this day, the Mormon lawmaker, whose affinity for the Jewish people and Israel is legend, wears a “mezuzah” necklace given him, I believe, by Rabbi Korff.

Rabbi Korff was best known to the American public as “Nixon’s rabbi” – a title given him by President Richard Nixon himself, with whom Rabbi Korff developed a deep personal relationship. It is widely believed that the rabbi had an influence on Nixon’s strong support for Israel and on efforts to allow Soviet Jews to emigrate.

When the Watergate scandal broke in 1973, Rabbi Korff staunchly defended Mr. Nixon, founding the National Citizens Committee for Fairness for the Presidency. He admitted that Nixon had “misused his power” and that Watergate was “wrong,” but felt that the president hadn’t committed any crime and deserved to remain in office.

But Rabbi Korff’s early years were even more remarkable, bordering on incredible.

In 1919, a pogrom was launched by Christian residents of his birthplace, the Ukrainian city of Novograd Volynsk. Jewish homes were ransacked and Jews killed where they were found. Five-year-old Baruch’s mother Gittel fled with him and three of his siblings.

The little boy watched in horror as a rioter ripped his mother’s earrings from her ears and then murdered her. Writing 75 years later, Rabbi Korff averred that he had branded himself a coward for being too frightened to protect his mother. “My life ever since,” he wrote, “has been a quest for redemption from that charge.”

The activist life he lived reflected that quest.

In 1926, the surviving family members immigrated to the United States but, after becoming bar mitzvah, Baruch journeyed to Poland, where he studied in yeshivos in Korets and then Warsaw. Upon his return to the U.S., he attended Yeshiva Rav Yitzchak Elchanan, where he received semichah.

During World War II, Rabbi Korff, who had become an adviser to the Union of Orthodox Rabbis of the U.S. and Canada, and to the U.S. War Refugee Board, petitioned European dignitaries, U.S. congressmen and Supreme Court justices on behalf of Jews in Europe. He even held clandestine negotiations with representatives of Gestapo head Heinrich Himmler, ym”s, about the purchase of Jews from Germany.

One of his wilder exploits took place in 1947, when, working with the militant Lehi group (derisively called the Stern Gang), he plotted to set off bombs in London (placed and timed to prevent human casualties) in protest of British policy in Palestine, and to drop leaflets over the city from a plane.

The leaflets began: “TO THE PEOPLE OF ENGLAND! To the people whose government proclaimed ‘Peace in our time’: This is a warning! Your government had dipped His Majesty’s Crown in Jewish blood and polished it with Arab oil…” The pilot he engaged in Paris, however, tipped off authorities and Rabbi Korff was arrested. After a 17-day hunger strike, he was released, and charges against him were dropped.

After the war ended, Rabbi Korff continued his work on behalf of fellow Jews, presenting a petition with more than 500,000 signatures to the U.S. government, urging that Hungarian Jews be permitted to enter Palestine.

Eventually, he served as a congregational rabbi in several New England cities, and as a chaplain for the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health. I met him in his retirement, when he employed me to edit one of several books he had written about his experiences.

During that final Providence visit, he lay in bed holding a morphine pump, but was still engaged with the few of us who had gathered to pay our respects. I remember him asking us to sing Adon Olam, and we obliged.

And I remember, too, a phone call he took from Eretz Yisrael, from someone clearly distraught at the rabbi’s dire situation. When the choleh hung up, he explained that the caller was a kollel man whom he had been helping support for a number of years.

So Senator Hatch’s announcement brought me to the brink of a thought that I often think, about how astounding were the lives of some who preceded us.

© 2018 Hamodia