The evolution of “traditional” lies used over the centuries to persecute, exile and murder Jews into new and, so to speak, improved forms would be amusing were it not so dangerous.

During the years of the Black Death in the late Middle Ages, when death tolls in some towns were as high as 50%, the famously favored scapegoat was “the Jews,” thousands of whom were murdered, many of them burned alive, in the 1300s.

The conspiracy theory back then was that Jews had been poisoning wells in order to kill non-Jews. The theme of Jews as diabolical poisoners was updated in the 20th century by Joseph Stalin in his “Doctors Plot,” in which most of the medical professionals whom he falsely accused of plotting to poison government officials were Jewish. More recent years have seen sundry neo-Nazis accuse Jews of spreading new diseases; and even, more recently, genteel suggestions that polio outbreaks were caused by Jewish anti-vaxers.

Guess what’s back now… Poisoned wells!

“I’m very concerned about my water,” lamented Ms. Grace Clark, of Upper Saddle River, N.J., fearful of what a Jewish cemetery uphill from her home might do to her children. “My kids play” in a nearby brook, she explained, “all the time.”

“We are observing an environmental train wreck in slow motion,” was how Heather Federico of nearby Mahwah chose to characterize that planned final resting place for Orthodox Jews.

I don’t know if either lady was inspired by – or even aware of – the sordid history of blaming Jews for well-tampering.

What I do know, though, thanks to the alacrity of Yeshiva University’s Dr. Moshe Krakowski, is that Ms. Federico and two other concerned citizens quoted in a May 11 story in The New York Times about the Har Shalom Cemetery in Rockland County, N.Y., are regulars on the website of Rise Up Ocean County, the infamous New Jersey group that has been repeatedly called out, even banned for “hate speech” by Facebook, for antisemitic postings. New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy denounced the group for “racist and antisemitic statements” and “an explicit goal of preventing Orthodox Jews from moving to Ocean County.”

The Rockland County property at issue, the Times helpfully explains, is, at some 20 acres, “expected to become the largest cemetery in the country reserved solely for ultra-Orthodox Jews.”

Also upsetting some local residents is a mikvah under construction across the street from the cemetery.

Both developments were approved by zoning and planning boards. What they have in common is that they will make life (and death) easier for Orthodox Jews. And help attract them to settle in the area.

That’s not, of course, what the fearful New York and nearby New Jersey residents say is the source of their concern. Their health and wellbeing, they insist, is motivating them.

And indeed, it’s true that cemeteries contribute to ground and groundwater contamination.

Formaldehyde, menthol, phenol, and glycerin are just a few of the toxins that seep into cemetery grounds. Some 800,000 gallons of formaldehyde are placed in the ground each year due to “conventional” burials.

What the word “conventional” refers to, though, are burials that take place after embalming. And that often use caskets made of metals like copper and bronze, which can also leach into the ground. Jewish burials, of course, involve no embalming chemicals and only a simple, safely degradable pine casket. That is what is referred to as “natural” burial, and is entirely kind to the environment.

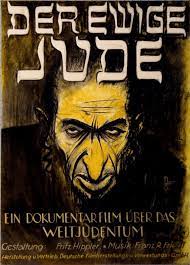

In 1940, the Nazi Ministry of Propaganda released the film Der Ewige Jude, “The Eternal Jew,” which became wildly popular in Germany and throughout occupied Europe. In one famously notorious sequence, it showed hordes of rats, which, the narrator explains, spread disease. “Just,” he continues, “as the Jews do to mankind.”

Popular broadcaster Tucker Carlson, fired in April by Fox News, recently appeared on a social media platform to rail against U.S. support for Ukraine and, in particular, against its Jewish president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, whom he called “a persecutor of Christians.” A weird charge, one not even Russian President Putin has made.

Mr. Carlson added his assertion that Mr. Zelenskyy is “rat-like.”

Well poisoning. Jews as rats.

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose – “The more things change, the more they stay the same.”

© 2023 Ami Magazine