As the school year winds down, parents and grandparents of Jewish elementary-age students are treated to… productions!

Things like Siddur and Chumash presentations accompanied by song and verse. There are plays about historical events and uplifting stories. And depictions of Jewish concepts like tefillah or brachos. This grandparent enjoyed a wonderful one last year that was focused on Shmitta and bitachon. (You and your schoolmates were great, Hadassah!)

And then there are the end-of-school-year “Ummah Day” productions at the Muslim American Society Islamic Center in Philadelphia, or “MAS.” They are somewhat different from their Jewish counterparts.

In 2017 and 2019, the children in MAS, as per videos posted on its Facebook page, sang “Chop off their heads!” about their perceived enemies, and expressed their eagerness to become “martyrs” in the cause of liberating “Palestine.” One little girl warbled, “I am a revolution that shakes the occupier. I am a wave on the calm sea. I hold my head high, and I will not be humiliated.”

The 2019 production, a joint venture between MAS Philadelphia and something called the “Leaders Academy,” received some 2 million views. After groups like the invaluable Middle East Media Research Institute (MEMRI) and the ADL, along with some American lawmakers, called attention to the issue, Facebook shut down the school’s page.

Subsequently, MAS Philadelphia and Leaders Academy released a statement expressing sadness over its “mistake” and contending that “antisemitism or other forms of bigotry are foreign concepts to us and we are especially saddened that our beautiful children and community continue to face these accusations [of hating Jews].” The groups pledged to “pave a positive future for our community and increase our work with people from all walks of life.”

Somewhat nonreassuring was the groups’ proud announcement at the time that they had “enlisted CAIR-Philadelphia to help us with a number of [sensitivity] trainings.” CAIR’s national executive director, Nihad Awad, has publicly called Israel a “terrorist state” that targets innocent civilians and declared that Israel “is the biggest threat to world peace and security.”

Which might explain why the sensitivity trainings didn’t work (or, perhaps, depending on the nature of the training, did). Because earlier this month, the little darlings at MAS were at it again.

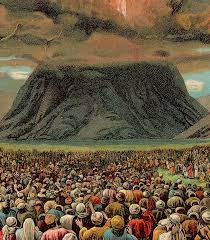

This time, the children at the school weren’t chopping off heads. But – in a video posted on May 6 by the Leaders Academy and exposed by MEMRI – they celebrated “One Ummah Day” with a song and performance praising “brave” Palestinian girls who support their “real men” as fighters against Israel.

One song describes a girl sending her brother off to battle and telling him: “I will saddle up your horse, and I will tie a dagger to your belt – enhance your resolve.” The video was also posted to the Facebook page of the Alhidaya Islamic Center in Philadelphia, another name for MAS.

Last week, a bill to address the problem of endemic anti-Jewish incitement in Palestinian Authority textbooks was unanimously passed in the United States House Foreign Affairs Committee.

California Democrat Brad Sherman, who introduced the bill, lamented the fact that the PA’s incitement contradicts American values of tolerance and peace, and noted that “For decades, the United States and the American people have been the top donor to the Palestinian people, including to the Palestinian Authority and UNRWA [United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine] – but this is not a blank check.”

“Unfortunately,” he said, “instead of envisioning a Palestinian state alongside Israel, the current Palestinian curriculum erases Israel from maps, refers to Israel only as ‘the enemy,’ and asks children to sacrifice their lives to ‘liberate’ all of the land between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea.”

In April 2021, the Biden administration defended its decision to restore financial aid to the UNRWA with the claim that the United Nations agency was committed to a “zero tolerance” policy regarding antisemitism. Unfortunately, that may have been pleasantly hopeful but it was patently false.

As a report at the time released by the IMPACT-se research institute revealed, schools run by UNRWA continued to teach hatred against Israel.

Incitement against Israel and Jews in Palestinian textbooks is reprehensible.

It’s even more reprehensible in an American school.

And irony is added to reprehensibility when such hatred sets down roots in the City of Brotherly Love.

© 2023 Ami Magazine