I began haphazardly collecting the advertisements a number of years ago. The first, which appeared at the end of Tammuz in a Jewish periodical, touted an eatery. It was apparently aimed at carnivores troubled by the restrictions of the imminent Nine Day period of mourning over the Bais Hamikdash’s destruction. Beneath a photo of a full plate of food was the legend: “Siyum Nightly for Meat Lovers!” Really.

More recently, I was struck by a full page come-on just around this time of year featuring a bottle of kosher for Pesach potato-based vodka over the legend: “Finally, shulchan oreich is a pleasure.”

Finally? I dunno. Somehow, my family’s sedarim have been immensely pleasurable, even vodka-free.

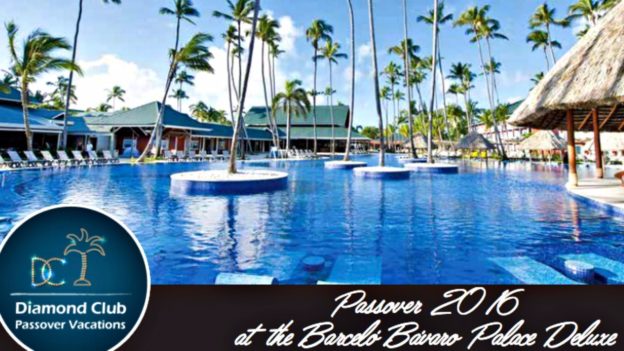

Between those offensive bookends I incredulously encountered many other Jewishly tone-deaf ads, in print or pixels. Like one advising how you can “steal the show” with some fancy table adornment or another; another one that proudly announced an all-you-can-eat “Fleishfest!” (though for a worthy cause); yet another letting the reader know that there’s a way to “Experience the real simchas yomtov,” by spending Pesach at a particular hotel. (Who would want a fake simchas Yom Tov, after all?)

And then there was the ad (for another away-from-home holiday locale) assuring us that “The only thing you should have to give up for Pesach is chametz.” Presumably, the message was that one shouldn’t have to spend his hard-earned free time – the holiday, after all, celebrates freedom, no? – cleaning, changing over the house and cooking for Yom Tov.)

And Sukkos really seems to bring out the best (so to speak) in Jewishly clueless marketing.

One late summer ad for a labor-free temporary tabernacle offered to end, once and for all, the dreaded “hassle of sukkah”; another dangled the lure of a getaway to a Florida Keys hotel featuring its own “air conditioned Sukkah!” (Good she’eilah there: If the AC is too strong, is one considered a mitzta’er?) And yet another invited readers to a glatt kosher vacation for the Yom Tov in the Bahamas, assuring them that “Sukkot Never Got This Good.” (After inviting Ushpizin, one supposes, he can, as the ad continued, “swim with dolphins!”)

That particular advertisement went on to modestly self-identify as “the most luxurious and extraordinary resort on Planet Earth.” Remind you of “So that your generations may know that I made the Bnei Yisrael dwell in sukkos when I brought them out of Eretz Mitzrayim” (Vayikra 23:43)? Me neither.

We Jews in America today are beneficiaries of Hakadosh Baruch Hu’s kindness beyond measure. We live in a time and place where we are not persecuted, have freedom to practice our faith and to engage in professions and businesses without hindrance –seldom if ever the case in our previous sojournings in galus.

But with plenty come plenty of challenges. The Shabbos before last we read in shul of the egel hazahav, the Golden Calf. It was said in the yeshiva of Rabi Yanai that Moshe attributed that sin to Hashem’s having bestowed much gold and silver on the people (Berachos 32a). It’s hard to be poor, but wealth carries dangers of its own.

I don’t want, chalilah, to injure any Jew’s livelihood, and have nothing against meat (though the less of it one eats, it’s increasingly clear, the better) or vodka, kosher for Pesach or otherwise; I’ve been known to occasionally splash a bit in my grapefruit juice myself. And there may well be people who, nebbich, need to spend Yomim Tovim in hotels.

But none of us should covet any of those things – or seek to stir covetousness for them in our fellow Jews. And, no less than we care about where our children receive their educational instruction we should care about the “chinuch” they receive from the pages of the periodicals we welcome into our homes. And we shouldn’t be sheepish about letting advertisers know when we feel their blandishments have crossed lines.

Yes, yes, I know that advertising is part and parcel of contemporary business, and what keeps Jewish papers and magazines afloat. But there is a stark, qualitative difference between ads that offer information, opportunities and products, on the one hand, and those, on the other, that shamelessly exaggerate – or, worse, that promote values that are, politely put, less than consonant with Torah-informed values. Or, worse still, that promote violation of one of the Aseres Hadibros’ “Thou shalt not”s (see “steal the show,” above).

There is ample room for creativity – photographic, linguistic, humorous and otherwise– in producing memorable advertisements for most anything. A Jewishly responsible ad doesn’t have to be bland.

But it should be becoming.

© 2018 Hamodia