It took years of complaints (mine among them) to The New York Times to get the Old Gray Lady to stop referring to Har Habayis as where the batei mikdash were “believed to have once stood,” and to respect reality by stating that “it is the site of two ancient temples.”

The paper even ran an “editor’s note” a few years back to clarify that “the headline and a passage” in an article had “implied incorrectly that questions among scholars about the location of the temples potentially affected Jewish claims to the site”; and that “unlike assertions by some Palestinians that the temples never existed,” there are no archeological findings that “challenge Jewish claims to the Temple Mount.”

Shkoyach. Chalk one up for history!

Unfortunately, the Beis Hamikdash doesn’t currently stand where it stood and where it will. And when the Har Habayis was captured along with the rest of Yerushalayim by Israel in 1967 during the Six-Day War, the Israeli government gave administrative control of the site to the Jordan-based Islamic trust known as the Waqf.

In keeping with the longstanding status quo that had prevailed until that point, Israel declared that only Muslim worship would be permitted on the Temple Mount. Israel’s leaders reasoned that changing the character of the site, where two Islamic edifices, the Dome of the Rock shrine and the Al-Aqsa Mosque, have long stood, would be seen by the Muslim world as a blatant affront. And so, to keep the peace, Israel allows only Islamic worship on the mount.

From a purely reasonable perspective, of course, prohibiting Jews from praying at Judaism’s holiest site is an absurdity. Reasonable perspectives, however, are rarities when it comes to the Middle East, and absurdities abound.

Israel’s decision to not change the character of the Temple Mount, discomfiting as it was, and remains, evidenced sensitivity and wisdom.

Neither of which are evident in the ongoing attempts by some to assert a Jewish presence on the Har Habayis.

Increasingly, groups of Jews have ascended the Har Habayis and prayed there. They are motivated, no doubt, by fealty to history and Jewish pride, but their actions, nonetheless, are provocations. And gifts to Muslim extremists the world over who loathe Israel and Jews, and who are on constant lookout for any event, however tenuous, that they can portray as insulting to their faith.

And indeed, each time a group of Jews enters the compound, Arab media screamingly condemn what they laughably call “stormings” of the site.

No, they’re not stormings. But neither are they justifiable.

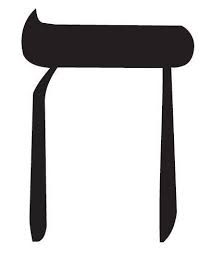

The “stormers” reject the opinion of gedolei Yisrael and the consensus view of Israel’s chief rabbis that Jews are barred by halachah from entering the compound. In 1967, the Israeli Chief Rabbinate ordered that a sign be posted at the Mughrabi Gate, the entrance to the Har Habayis for non-Muslims, warning that “According to Torah Law, entering the Temple Mount area is strictly forbidden due to the holiness of the site.”

But even those who rely on minority halachic rulings they say permit them to stand on part of the compound need to realize that not everything that’s permitted is necessarily wise. And asserting a Jewish presence on the Har Habayis today, in the context of raging global Israel-hatred, most certainly is not. The ascenders to the mount might feel inspired by standing on the holiest ground on earth, but there are 2 billion Muslims who, to put it delicately, don’t want them there.

Most recently, a small group of Jews entered the compound carrying a “Guide Page for the visitor to the Temple Mount,” newly published by the “Temple Mount Yeshiva.” Alongside instructions for visitors, the page pointedly includes the Shemoneh Esrei.

The man who heads the Temple Mount Yeshiva told Haaretz that he hopes the next stage will be the introduction of regular siddurim, and Jews wearing taleisos and tefillin.

To be sure, a new era of history will ensue when, in the navi Yeshayahu’s words, “a wolf and a lamb shall graze together,” when the entire world will recognize that Moshe emes viToraso emes.

But we’ve clearly not arrived there yet. And, in the interim, we are enjoined to not goad or incite other peoples or religions. That directive might be vexing, but doing the right thing often is.

(c) 2016 Ami Magazine