Last week, New York mayor-elect Mandani not only demonstrated, once again, his hatred for Israel, but also lifted the hood on the engine of his animus: an abysmal ignorance of both history and law.

To read how, click here:

Last week, New York mayor-elect Mandani not only demonstrated, once again, his hatred for Israel, but also lifted the hood on the engine of his animus: an abysmal ignorance of both history and law.

To read how, click here:

Yaakov famously sequestered Dinah his daughter in a box as he prepared to meet his brother Esav.

That, according to the Midrash Rabbah brought by Rashi (Beraishis 32:23). His reason for hiding Dinah, the Midrash notes, was because he feared that Esav, upon seeing her, would wish to marry her. And Yaakov didn’t want to take that chance.

There’s a phrase in the Midrash, though, that is easily overlooked but shouldn’t be. Not only did he put his daughter in a container, he “locked her in.”

What that seems to indicate is that Yaakov knew that, as Chazal explain at the very beginning of the saga of Dinah’s abduction and rape by Shechem, she was a yatzanis, an “outgoing personality.” She was a naturally curious person. And so, prudently, her father locked her in, since he feared she might emerge during his meeting with Esav to witness the goings-on and be targeted by her uncle.

And, according to the Midrash, Yaakov is faulted for that, since, had Dinah in fact been seen by Esav and ended up marrying him, she might have been able to turn his life around and alter the enmity he held in his heart for Yaakov.

But protecting children is a parent’s first priority. Wasn’t Yaakov right to do what he did?.

Apparently not. The question is why.

What occurs is that children have natural proclivities and tendencies. There are times, to be sure, indeed many times, when a child has to receive “no” as an answer.

But squelching a child’s nature is not a good idea. It can easily backfire. Ideal child rearing is channeling the child’s nature, not seeking to squelch it. (See Malbim on Chanoch lina’ar al pi darko in Mishlei 22:6).

My wife and I know a couple whose little boy seemed obsessed with airplanes, beyond the normal interest in such things shared by all little boys. The parents didn’t try to dissuade him from his desire, as he grew, to fly or work with planes, to force him, so to speak, into a box. They allowed him to express it, and the little boy is grown today, a yeshiva (and flight school) graduate who is a certified air traffic controller, and he’s raising a beautiful, Torah-centered family with his wife, our daughter.

© 2025 Rabbi Avi Shafran

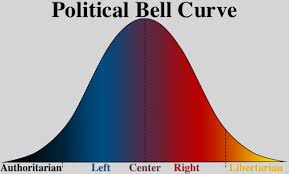

I’m as chagrined as anyone about the ugliness we are witnessing on the extremes of both American political parties. But there have always been isolationists and bigots in Congress.

Does a respectable mainstream, at least presently, dominate in each party?

My take is here.

Some people’s default attitude in life is “I really deserve more than I have”; others are prone to feeling that “I really don’t deserve what I have.”

Most people fall somewhere on the spectrum between those two extremes, and most people also may experience one of the attitudes at some points; the other, at others.

Menachem Mendel of Kotzk, the Kotzker Rebbe, pointed out that, even though Jews are descended from 12 tribes, the sons of Yaakov, we are called Yehudim, after only one of those progenitors, Yehudah.

That, he contended, is because Jews are meant to embody the sentiment that yielded Yehudah his name – his mother Leah’s declaration at his birth that she was the beneficiary of what she “didn’t deserve.”

Since Yaakov had children from four women and Leah knew that her husband was destined to father 12 sons, she expected to bear only three. Yehudah was her fourth. And she acknowledged (“odeh,” the root of “Yehudah”) the fact that she had “received more than my share” (Beraishis 29:35; see Rashi).

Traditionally, the first words to leave a Jew’s mouth each morning upon awakening are “Modeh Ani” (or, for a woman, “Modah Ani”) — “I acknowledge.” The acknowledgment is for having woken up, for life itself. A Jew is meant to take nothing for granted, nothing. To take everything he has as a divine gift.

© 2025 Rabbi Avi Shafran

While the world watches to see whether the tunnel-ridden wasteland along the Mediterranean called Gaza can be restored to a livable place, what can’t be ignored is the most important part of the reconstruction effort: the rebooting of the Gazan mind.

To read more about that, click here.

Yaakov’s middah – defining characteristic – is emes, truth, and so Rashi parses Yaakov’s misleading words to Yitzchak to make them true on some level. For instance, allowing his father to believe it is Esav to whom he is speaking, Yaakov says “I am Esav your firstborn.” Rashi interjects a presumed pause in the sentence, rendering it “I am [the one bringing you food]; Esav is your firstborn” (Beraishis, 27:19).

Yet one misleading phrase still stands out: “Come eat of my hunted [food]” (ibid), says Yaakov, offering his father the goat meat he could mistake for game. But it was neither Yaakov’s food – his mother Rivka had prepared it – nor had it been “hunted.” How was Yaakov not lying?

What occurs is that “hunting” is a word we’ve seen earlier, in the Torah’s description of Nimrod: “a powerful hunter” (ibid 10:9). And there, Rashi explains that what Nimrod “hunted” and captured were people’s minds. He used words and subterfuge to mislead, convince and amass followers.

Perhaps here, too, Yaakov was subtly, slyly, subtly “confessing” to his father that he was engaged in a psychological subterfuge, presenting himself as someone he wasn’t, offering his “hunting” to Yitzchak, his ability to navigate a tricky and untrustworthy world. Thereby demonstrating that he, Yaakov, too, was capable of dealing with that challenging world no less than his brother, something that, as the Malbim and others explain, Yitzchak had assumed was not true.

And so Yaakov was saying, in effect, “Accept my current subterfuge as proof that I can do what you have assumed only Esav is able to do.”

© 2025 Rabbi Avi Shafran

Dear Visitor,

I have started offering weekly writing on the online publishing platform Substack. What I post there are either ruminations that have not been published (or are unpublishable!) elsewhere, some oldies but goodies (at least in my estimation) articles and short thoughts on current events. There is no charge for subscribing.

To subscribe to receive the offerings, just go to https://substack.com/@rabbiavishafran

and click on the “free” option. There is no need to upgrade to a paying plan (though any funds generated will go to help marbitzei Torah — like funds generated by the “Donate” button here). All of what I post will be accessible to all subscribers.

It’s human nature, when faced with something tragic, or even just disturbing, to say to oneself, “If only…”

“If only I had done this… or we had done that… or not done this… or not done that, we could have avoided this outcome.”

But human nature can be misleading. A thought I once heard suggests that the repetition of the phrase, “the years of Sarah’s life,” in the first pasuk of the parsha, even though the pasuk had opened with “And the lifetime of Sarah was 127 years,” teaches us to resist our proclivity to imagine that things could have been different had we only acted differently.

We might think that had Sarah not been told (as per a famous Midrash) about her son having been bound on an altar, she wouldn’t have died at the moment she did, having been spared the shock.

But Sarah’s death was divinely ordained for that moment. “The years of Sarah’s life” were the years granted her. The proximate cause of her death wasn’t its ultimate cause. Its ultimate cause was Hashem’s will.

Post-facto calculi in such things are wrongheaded.

We are certainly required to do what is normative practice to preserve our health – but only that. Someone, for instance, who suffered from Covid when it was raging might kick himself for having worn only a simple mask, not an expensive, surgical-quality one. Or for having spaced himself only 6 feet from others, instead of 10. But if one fulfilled the normative obligaton and still became sick, he is wrong to agonize over not having done more. He needs to recognize the ultimate determinant: Hashem’s will. And then do what normative practice demands, to, with Hashem’s help, recover.

But pondering “if onlys” is pointless.

© 2025 Rabbi Avi Shafran

Remarkably, in response to Avimelech’s protest over being punished for taking Sarah, Hashem confirms the king’s insistence that he had acted innocently, believing that Avraham and Sarah were, as they had claimed, brother and sister.

“I, too, knew,” Hashem tells Avimelech in a dream, “that it was in the innocence of your heart that you did this” (Beraishis, 20:6).

So, if Avimelech was innocent in taking Sarah, why didn’t Hashem merely prevent the king from approaching her? Why were he and his family and entourage physically punished?

Perhaps the answer lies in what Avraham told Avimelech, when the king demanded an explanation for having misled him:

“Because,” Avraham explained, “I said ‘There is no fear of G-d in this place’” (ibid, 11).

A leader, that tells us, has the ability, and responsibility, to influence the mores of his society. And if a society evidences lack of “fear of G-d,” its leadership is implicated in the evil.

A piece I wrote about President Trump’s nominee for ambassador to Kuwait is at Religion News Service and can be read here.