In the current polarized political atmosphere, where “team” mentality – “our guys are great, yours are bums” – seems to be the default state of mind, and where objective, thoughtful fairness is the rarest of birds, it must be particularly hard to be a black conservative Republican.

Like Justice Clarence Thomas, Stanley Crouch and Thomas Sowell before him, Dr. Ben Carson, the once-presidential candidate and now Housing and Urban Development Secretary, was recently reminded of the perils of that identity, when an entirely innocent comment he made was blown out of all proportion by a horde of players from Team Black and Team Democrat.

As he began his first full week leading HUD, which provides housing assistance to low-income people and development block grants to communities, and enforces fair housing, Dr. Carson spoke to a standing-room-only audience of the agency’s employees.

He praised them for their dedication to HUD’s mission of “helping the downtrodden, helping the people in our society to… climb the ladder.” And then he extolled the United States as a land of opportunity, saying: “That’s what America is about. A land of dreams and opportunity. There were other immigrants who came here in the bottom of slave ships, worked even longer, even harder for less. But they, too, had a dream that one day their sons, daughters, grandsons, granddaughters, great-grandsons, great-granddaughters might pursue prosperity and happiness in this land.”

The positively lupine reaction to that eloquent paean to America was to pounce on Dr. Carson’s pointedly loose use of the word “immigrant” with reference to African slaves brought to these shores in the 18th and 19th centuries. From the overheated comments that suffused the media, one would have thought that the doctor had extolled slavery rather than the aspirations of slaves, that he had made a direct comparison rather than a clear contrast.

Pundits and academics across the land rent their garments at the desecration, and Congressman Keith Ellison of Minnesota railed that Dr. Carson had shown a “stunning misunderstanding of history… a very scary thing,” and declared that the doctor’s perspective makes him unqualified to lead HUD.

I don’t know what sort of president Dr. Carson would have made, had he prevailed in the Republican primary. He certainly showed misjudgment by imagining that civility is something appreciated by the American electorate.

But I find it easy to envision that he might be just what an agency like HUD needs: someone who recognizes that, however dismal one’s past was or one’s present is, the healthy attitude is fortitude, seeing opportunity in the future and recognizing the role one can play in his own destiny.

Dr. Carson’s personal story exemplifies that well. A poor student in Detroit with, by his own recounting, an anger management problem, he “ask[ed] G-d to help me find a way to deal with this temper” and studied Mishlei. The passuk, he says, that spoke to him most powerfully was “Tov erech apayim migibor…” – “Better a patient man than a mighty one, [better] a man who controls his temper than one who overtakes a city” (16:32). He set himself to the task of self-improvement and earned a full scholarship to Yale, working summers as, variously, a clerk in a payroll office, a supervisor of a crew picking up trash along the highway and on an assembly line. At Yale, he worked part-time as a campus student police aide.

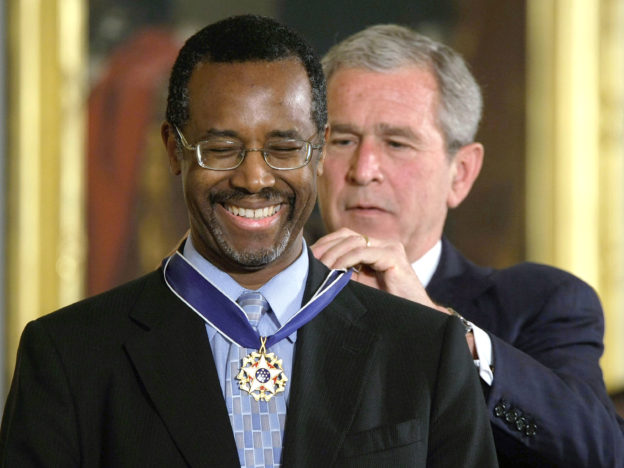

In 1984, when he was 33, Dr. Carson became the director of pediatric neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins University, the youngest doctor in America at the time to hold such a position. And he went on to distinguish himself, pioneering groundbreaking surgeries and receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor in the U.S., in 2008.

Interestingly, an American president, during a naturalization ceremony at the National Archives, made a similar point to the one that earned Dr. Carson such opprobrium.

He said that “Life in America was not always easy. It wasn’t always easy for new immigrants. Certainly it wasn’t easy for those of African heritage who had not come here voluntarily, and yet in their own way were immigrants themselves… But… they no doubt found inspiration in all those who had come before them. And they were able to muster faith that, here in America, they might build a better life and give their children something more.”

That was Barack Obama, in 2015.

Dr. Carson, in his speech, pledged to lead the agency with an “emphasis on fairness for everybody… complete fairness for everybody.”

How shameful that fairness seems to utterly elude the “team players.”

© 2017 Hamodia